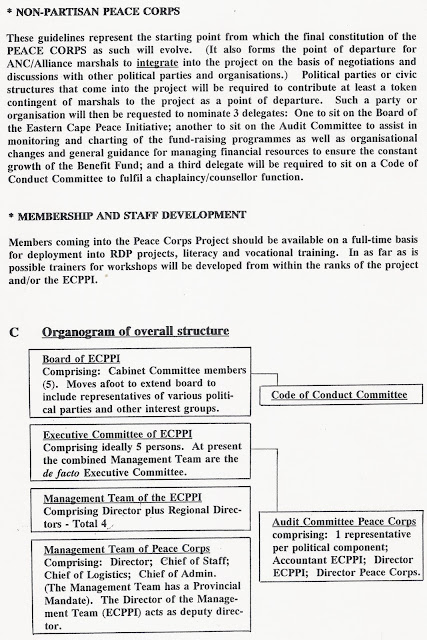

Bodegraven Church

Most

of the narrative writing on the origin of the Dutch Anti Apartheid Movement (AABN) outline its history as having commenced with its

amalgamation between the Comite Zuid Afrika (CZA) and a loosely defined student group of upstart students. Sometimes this is portrayed as

having been an aggressive “takeover” of the CZA by a group

of rebels from the "socialist" Gemeentelijke Universiteit Amsterdam. Given the character and scale of student rebellions impacting on almost all main universities in Europe and the US trepidations among many observers were understandable. While tens of thousands partook in marches and demonstrations on the streets, and radical actions like the occupations at Universities were the order of the day, outside observers stood in awe of these establishment-shaking events and looked on in dismay as an old world order seemed to be collapsing around them. Yes, these were the 1960s, flowering in the early 1970s with many present day grey-haired academics claiming part of the action and even authorship of the massive social movement that exploded four decades ago. While it is true that there were many social writers whose ideas became fashionable and had catalytic effects, these were not by design to prefigure "revolution". Many critiques of both western capitalism and eastern communism were spot on and fed into, rather than caused the revolutionary upsurges. Jean Paul Sartre was going out of fashion, and what became known as the critical theorists (Frankfurter Schule) had great impact. Revolution was upon us, plain and simple, much like the Arab spring of yesteryear. However, like can be expected from subsequent social upwellings, including the fall of Apartheid, revolution anywhere soon is further way than ever and as yet never consummated.

While the old veterans of the ANC today speak about the Anti Apartheid Movement having been the greatest thrust in the 1960s uprisings, the reality is that radical thinking during those days regarded Apartheid a civil rights byline, never taken seriously by radicals as a "front line for revolution". For this to happen the ultra orthodox role of the through-and-through Stalinist South African Communist Party stood in the way. In the US for example, Alan Paton was well known, as well as is Nelson Mandela today. Beyond the university rebellions there were "third world solidarity groups", saving pennies to buy food for the starving in Biafra and other poor countries, but these were generally regarded as "Sunday School" groups.

So this intervention of radical students in an established anti apartheid organization and turning it upside down was rather unique. A booklet written by Kadar Asmal, commissioned by the UN Special Committee on Apartheid, on the status of the Anti Apartheid Movement internationally bears this out. Published in 1975 Asmal made special reference to the AABN as the most radical and vibrant Anti Apartheid group, also mentioning that in other countries where radicalism was the order of the day the Anti Apartheid Movement was shunned as a poor cousin and preference given to involve with the anti Vietnam War or Palestinian solidarity movements.

What most observers miss, especially those who are in charge of archiving material relating to Anti Apartheid of the period, is the prefiguring role and ideological character of a student group within the broader Amsterdam student movement that played an interlocutor role to bridge the gap between itself and the CZA. This was not a process of design, let alone the culmination of a coup-driven motive of a few students, but a spontaneous rise of a radicalised AABN drawn into the whirlpool of radical events. There was clear break in continuity of the CZA to the AABN and a dramatic

radicalization of its work after a small group of “rebels”, a group named PLUTO active at

the University of Amsterdam, became active in the old CZA. What hit the established order in general with the gusts of renewal in the Netherlands, also hit the CZA from within. Considering the CZA it is

symptomatic of such organizations grounded in establishment interests to become

moribund, lose direction and settle out in some form of vertical management structure

where establishment interests take over direction and

determination of programmes. There was no "Damascus conversion" with the leaders of the CZA, but agency work from the radical student movement that impacted on ideological postures and programmes within and outside of the University. The reality was that PLUTO filled a gap. Had it not done so the CZA would have gone over the cliff and fallen into oblivion. Its salvation from oblivion was partly by serendipitous events, partly by default, and partly an organic process explained by none better than Antonio Gramsci.

So

certainly, after the “merger” of the CZA and the student group (PLUTO) there

was an immediate galvanization which became palpably visible to the Dutch

public. Press reports on actions which shook up the traditional CZA

constituency hit as if from nowhere taking the rather massive membership of the CZA membership by complete surprise. There was initially a haemorrhaging of CZA members which was reversed once the AABN won media and institutional respect from left political parties. It was nevertheless unfortunate that the "barbarian irruption" caused friction which spilled over into resignations of key members of the old CZA board, like Professor Willem Albeda. Also being a radical movement secured in its own public space, it was unfortunate that some political parties vied to "take over" the original domain of the AABN. An initial

contention concerned the stance on economic sanctions Against South Africa.

While the idea of sanctions was not foreign with the people of the CZA as they

were receiving much, if not all their information from the London-based Defence

and Aid Fund as well as the British Anti Apartheid Movement (AAM), when the

internal turmoil struck the CZA there were contentions to ensure that sanctions

would not form the main thrust of the new AABN. Professor Willem Albeda, a developmental economist at the Economic High School in

Rotterdam, published an article on how stupid and short sighted economic

sanctions against South Africa were. He made a powerful argument

that economic growth erodes Apartheid rather than undermines it. Remarkably, in the Dutch Labour Party and Trade Union component in the old CZA, there was a similar caution voiced by the British TUC that sanctions must not be at the expense of Dutch or British jobs for workers. Sanctions against industrial goods import and extorts were out; consumer boycotts were okay.

In conclusion, what has been portrayed as the "CZA being hijacked by radicals", was a perception and nothing more. What was going on in the entire Netherlands and Europe generally, was a buckling of establishment organizations that

were too hierarchically organized and glued together by ancient mores and practices. This was to a certain extent the case with

the CZA. For the CZA to be against injustice in a far off land was okay. But keep out of sanctions that will cost Dutch jobs. In the case of the British AAM the same applied but with an additional complication. While the original Anti South Africa Movement in the UK was started by Jamaican emigres as a means to deal with racism in the UK, once the ANC hijacked the group the new Anti Apartheid Movement in the UK made a specific point of sticking clear of local, British racial issues. Reform in in a far away place was okay; but not in the British Backyard. Likewise, having any connection with the troubles in Northern Ireland was double trouble even though a considerable group of British Based Anti Apartheid activists did become active in the British Troops Out of Ireland movement. But they were isolated and scorned by a new type of dictatorial hierarchy whispered by background noises of the SACP. On the otherhand what the CZA wished to keep out of the front door, entered from the back and below.

The so-called “1968” movements, best represented by the uprising of students

in Paris in 1968, was a wave of social unrest and reform that swept hither and thither,

winds of change that were flattening out hierarchical structures wherever these

stood in the way of people striving for an open democratic society. There were a number of characteristics in this movement which

went viral. First, it was bottom up. Students, workers and even middle

class people, felt that too many decisions were concentrated and taken in

secret, over and above them. Their key demand was participatory democracy as

a minimum, or a full re-engineering of establishment organizations as

cooperatives as a most ideal objective. While there were a few massive movements that kept the momentum going, such as the anti War Movement Vietnam, in general the politics was limited to forming loose coalitions of like minded groups. Small autonomous groups converged for happenings and then dispersing when these were over. Keeping engaged on issues on the ground was the lifeblood of a movement which to many like myself, was thought to spring eternal Interspersed in the movement were small nodal groups that became the bugles for large assemblies, to gather around, mandated to organize massive happenings, and speak into developments which

had boiled up reflected mainly the inhumanity of war in Vietnam. It

was the time where the watchword was catalyst action groups driving for a

fundamental democratization of society and toppling establishment hierarchies. The movement swept across from university to university, from labour movement to labour movement across borders like a raging tornado wherever there were democratic deficits acting like low pressure points attracting the next blast of raging winds of change. In the summer of 1969 the students opposed the undemocratic structures in the University of

Amsterdam and occupied its administrative complex; in May 1968 the uprising in Paris causing a near-revolution and total collapse of state authority. Ultimately the aim was a total democratic transformation of society.

The

students union at the Amsterdam University (ASVA) played a central coordinating

role among a whole variety of action groups, mostly organized within the

different faculties. But there was no group that was dominant, let alone

hierarchically organized, which took decisions and passed these down networked

groups small or large. The foot soldiers called the tune. Among these

groups that formed within the student movement was the Aktiegroep Ekonomen, a

group whose ideas went viral and resulted in the occupation of the economics faculty of the University. This move set in

motion reading groups to replace formal classes and curricula for an alternative what had been bequeathed by centuries of stale bureaucracy. And within this group again, a small group

formed called PLUTO that discussed and kept tabs on economic developments

especially with regard to the decolonisation process.

Another

characteristic in the movement was the tendency for groups to interact on an ad-hoc basis, sometimes longer term or even merging efforts. In the

case of PLUTO the first kindred group which to interact between separate centres of learning was the Rhodesia Committee, set up

by students at the Amsterdam Technical High School. Another group to come onto

the scene was the Socialist Youth (SJ), a radical youth group of the Dutch

Labour Party. The SJ had contacts with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and subsequently abandoned by their mother body. So radicalism against Apartheid in Africa was okay; but solidarity with the people of Palestine was not okay. Each group had to navigate its own waters and some, later many, fell victim to state repression. But all shared the spontaneity engulfing and sweeping together radicalism and even though engulfed by neoliberal reaction and smother for a few decades, the movement kept germinating in periods, first Seattle, then more issues inflaming human dignity regarding climate change, mass march against the powers that were huddled together in the W$$D in Johannesburg 2002, then the Arab Springs, currently the emergence of the massive occupy movement.

It

is difficult to make a statement like, the 1968 movements were

basically Marxist. Yes there were a few staunch Marxist groups, the Aktiegroep

Ekonomen for example, which remained small and limited to members in its own

immediate terrain but not characteristic of the student movement as a whole. The more ideologically clear groups did however tend to give direction and build momentum in the overall movement. Individual groups had their own specific aims and interests but united in one effort as and when situations developed. Occupying the administration of the University of Amsterdam involved the entire movement. Common interest in literature provided the glue with Marcuse, Gramsci, Lucacs, Adorno, Fanon to name but a few, became international currency in radical circles. In

the early 1960s, before the 1968 explosions, there were other authors and groups vaguely having the same impetus and popularity. Jean Paul Sartre was more or less dominant in the earlier postwar period. Also important was a blossoming of the Situationist

International (SI) inspired by the French philosopher Guy deBord, with

flamboyance displayed in a new genre of activism. In Amsterdam groups arose in alignment with the SI to form the PROVOs who won seats in the municipal elections. These action groups focused on creating spectacles, like planting

flowers on the roof tops of trams and buses, closing off streets and blocking

out motor traffic, women groups like the Dolle Mina who had their own special

ludicrous ways to demonstrate women’s power on the streets. And of course the PROVO's did not sustain in the municipal government as their only aim was to make that structure appear what it was, a ridiculous farce. In the later

sixties the SI became less visible but threads of their thinking imbued

ideological movements quite extensively. The spectacles were conceived to counter images created

in the mass media and consumerism generated by the corporate world. Consumerism was understood to determine relations between human

beings. In a way this early stream of activism can be seen to be manifesting itself

with the current OWS mass movement. Barring of course that the OWS takes the bull by

the horns, the dragon by the throat and goes directly at the super rich rich. The Occupy Wall Street is spectacular, a spectacle that may come to overshadow any other before it.

The

rise of PLUTO as an informal group in this complex of autonomous action groups was very much the way movements developed in the 1960s and 70s. Ultimately these movements surged and shook the establishment throughout the Western worlds. True, with the merger of PLUTO and the CZA a lot of the CZA’s establishment

character withered as the autonomous nature of PLUTO impacted, but ultimately the AABN fell victim to establishment influences all the same. There

were many U-turns that had to be made in the process of PLUTO’s further development in the framework of a more establishment-type AABN in later years.

Actions spilled discussions, were broad ranging and hardly limited to South Africa. The

continued exploitation of the Third World countries beyond naked slavery and

colonial empires was a subject that was much informed by Frantz Fanon, and epitomised by the coup engineered by the US in Chile. In

Europe the struggle of the Algerians was much closer to home than the struggle

in South Africa. And of course, the War in Vietnam dominated mass movement altogether.

The struggle of the Northern Irish was much more an issue in Europe than South

Africa. No movement in Europe ever took “armed struggle in South Africa

seriously; the struggle in South Africa was perceived as a Civil Rights

struggle, much the same as in the United States. The single issue espoused by the CZA had to give way in a process that probably only comes to fruition in the aftermath of South Africa's birth of democracy. What we thought we were fighting for was not what we got. And yet, precisely because of the core of the Anti Apartheid Movements being a limp and ineffective ANC, the Anti Apartheid Movements thrived precisely because of that. Taking the Irish question forward, on the other hand was declared anathema by the establishment meda and state. When Chile fell in the first really aggressive blow of the neoliberal agenda it was widely spoken of but not much happened to unseat Pinochet.

For the AABN and the Anti Apartheid Movements generally, the

imposition of the “armed struggle against Apartheid” outflanked other issues, like Chile, Latin America in

general, Palestine, especially after the Americans were kicked out of Vietnam.

One wonders whether this was not a grand strategic design of the British to

focus on one issue at the expense of others, and especially divert attention

from the liberation war going on in its own backyard in Northern Ireland. Or to keep the lid on its own immigrant population in Britain. It is

therefore also no wonder that the mass media has glorified Nelson Mandela as

the “Martin Luther King” of South Africa. What has become of the “armed

struggle” led by the ANC / SACP has become a basket of plastic heroes and

nowhere has there been a comprehensive history written about the actual South African

Armed Struggle. The reason is that there never was such a thing as an ANC armed struggle, in any case not much further than a few odd bombs thrown and the killing of a few policemen. Or the heroics of a maverick MacBribe who threw a bomb into a Durban restaurant but recently unmasked as a thug and a drunkard. There is in

fact much more to hide, like the ANC detention camps for its own members in Quattro. Today we have the glorification of this mythological armed struggle continuing in an attempt to impose the ANC hegemony in a "nation building" project. It’s a very superficial hegemony project to

maintain the dominance of the ANC as a liberation movement belied by its

negotiated Western-style democracy, warts and all. Armed struggle, in the words

of Ronnie Kasrils, was armed propaganda. In the aftermath of democratic

elections held in 1994 the basic character of the South African state remained

unchanged. Armed struggle has been reduced to a myth and too many public

holidays. And yet, in recent years there are anything up to to 10,000 internal protests for lack of service delivery, lack of houses, generally speaking totally dashed expectations broadcast so loudly by armed propaganda. And some 10% of these internal protests turn violent and broken up by an increasinglt more aggressive and unskilled police force.

The

merger between the CZA and PLUTO, and especially when it became clear that the

CZA itself was under the thumb of the AAM in London, was really a matter of

expedience. Professor Albeda advanced a well

thought out argument that in effect turned out to be prescient in the way that economic growth pressures led to

the fall of Apartheid and replacement by a more liberal but at the same time more cruel economic system. Albeda got slammed and soon he resigned from the redesigned CZA. Looking back at the early PLUTO

position on sanctions the criticism resulted in a more realistic

type of solidarity between unions on a country-to-country basis. Not that deep cutting economic sanctions was abandoned. The AABN approach led to a more aggressive implementation of sanctions than those applied in

London where it was limited to media and diplomatic action. PLUTO was dead against consumer

boycott actions. Here a leaf has to be taken from the American Civil Rights movement.

The rise of the migrant workers on vegetable and fruit plantations, under

leadership of Cesar Chavez, eventually enlisted public boycott support to bring

plantation owners to heel. This showed the way to go if similar actions were to

be undertaken in far off countries like South Africa. What PLUTO regarded as important was that the Californian plantation

migrants took ownership of their actions and carried the risks. Through their

FWU led by Chavez they had confidence and addressed challenges as a collective.

True, in South Africa trade unions were banned; but that means that much more

thinking of strategy should have been employed to encourage trade unionism

through international solidarity, rather than fighting their battlers without

their direct participation, difficult though that was. Here Oliver Tambo proves to be prescient in establishing Okhela as a white group to bring into the fold the main theatre of white activism inside South Africa, namely the many vanguards trade union cadres. The AABN principle was was that sanctions only make sense as extensions in building trade union solidarity.

But getting back to how PLUTO manifest itself initially. At

some point PLUTO, before its merger with the CZA, was approached by members of the SJ. They were proposing a

“happening” in a small town, in the deep South of Holland. Their plan

was to disrupt a South African water polo team which would be playing against a

local team. Welcome to Bodegraven, 1970,

to a small rural, with a mysterious history; sometimes being on the map,

sometimes not, and centuries ago an outpost on the northern boundary of the

Roman Empire. The town has a rich

mythology and many legends about wars, disasters and survival of a tough, very

conservative people. And today the town is most conservative and home to a

staunch Calvinist tradition. The SJ thought they had a mission there. If they were out to provoke and get a violent reaction they sure got it. This was

to be a spectacle with a purpose, to poke with a vengeance against a conservative, some said backward rural people. As the SJ put it, "the town had to be shaken out of its slumber

and brought into the modern world". Some members of PLUTO were mobilised and together

with a much larger contingent of SJ members the posse set out for Bodegraven by

motorcade, to somewhere between Leiden and Utrecht. The water polo competition had

to be disrupted and the intended tournament to be held throughout the

Netherlands smothered in the germ. On the spur of the moment the plan seemed

reasonable enough albeit adventurous. The

intention of the spectacle was to poke an ultra conservative Dutch community with a dubious past during the Hitler occupation,

and jolt the youth of Bodegraven to take an interest in social activism.

This

action took place with success, the game was disrupted but with a massive

unforeseen consequence. First, the Bodegraven youth were not quite the backward

folk we thought them to be. In any case not in the sense of having no feel for self defence, protection of their town against the "reds from Amsterdam". Not so backward to stand idly by and watch this

“intrusion” to go by unchallenged. They “counter demonstrated” their feeling of

ultimate insult at the intervention from "Amsterdam”. They fought

back and fought hard. They had the “intruders” fighting with their backs

literally to the walls and fleeing for cover in bush and ditches and even an

ancient little church. The scenes were amazing. The “intruders” were treated

like coming from the devil, their posters snatched, clothes ripped off, and

little piles of this “booty” taken outside the little church and set alight.

Little bonfires were made and it seemed that a barbarian invasion was

being stamped out in spectacular displays of wild dancing and running around

screaming.

But

totally unforeseen was the media impact of the PLUTO/SJ spectacle. Having had

success with the action itself, but having survived a bruising battle with the

local youth and what appeared to be a well prepared vigilante group, we

trickled back to Amsterdam by drips and drabs to behold that the news was

carried in great detail on all the TV News networks and daily newspapers the

next day. Getting publicity was seen as a reward for success. Good, soon many groups were out to make a name for themselves, gasin notoriety, spread their idiosyncratic messages, let me say newsworthy was soon equated with worthiness itself. Little did we realise that seeking media attention would, among developments on other fronts, be the beginning of a downfall of the 1968 social movements. This modus operandi can be related to the Situationist Internationalist who thrived on the idea that small groups can gain tremendous leverage by doing outrageous things and playing with the media impact. In short, as the "counter revolution" kicked off with many militants hardly realising it had, some were deformed by media images, some sections became establishment and

grew out to become government funded NGOs, some set up for co-option by the

very establishment manipulations that sparked their rise. Yet others were criminalised, members jailed and scandalized, most simply dissipated and the end of the 1970s the social movements of the mid

1960s/70s had lost momentum as social movements promising a better world that

seemed possible.

Almost

immediately after the Bodegraven spectacle we were called by the CZA. As PLUTO

was a leaderless group without at that time any public profile, flexible in memberships, in fact not much unlike the

Situationist International which mainly one guru with a litany of loosely organized admirers. Not that Okhela was quite like that, but in amplification pervaded a whole of revolutionary action groups. The personality cult was more than such a national phenomenon to be found in the Soviet Union. It also existed as opportunity seeking personality maniacs should to build and maintain their own little nooks as leaders of a "revolutionary group". Guy De Bord, probably was such a person. I offer wonder whether Breytenbach, who grew up ideologically in Paris, was not a Guy de Bord-type activist. Of course, later the so-called "Baader Meinhoff" group was what resulted of the revolutionary Red Army Faction: swallowed up by media slanders and spat out as a gang of very bad people.

Be this all is it may have been, Bodegraven swelled the PLUTO's media profile. For the CZA It was fear of being

outflanked in the media and made irrelevant that was cause for them call for

merger talks. The CZA needed a spice of revolutionary elixir and found that in PLUTO. But in return it was a kiss of death for PLUTO as the product, the AABN, gradually was swalloed up by other organizations, the funding from the Dutch Government, and ultimately gobbled up through infiltration by the South African Communist Party, poster movement for Soviet support of unadulterated Stalinism.

What

followed were piecemeal awakenings. The first was that we had not merged with

an autonomous group without legal or administrative consequences. We became

part and parcel of an existing organization which merely changed its name, but

was a registered organization and a considerable mailing list of donors.

Sanctions

were a divisive and controversial issue. There were many London-sympathisers in

Amsterdam who came out with all sorts of off-the-cuff remarks. Alan Boesak,

then a theology student made his disdain known that “a white South

African” is involved in the renamed CZA, the AABN. Funnily enough he poked, but

poked in a most peculiar way – to get at this “white South African” who had

apparently usurped his predominant position in the “anti apartheid movement” he set about circulating a petition against sanctions. With the PLUTO militants

there was heated debate. First the issue of taking money from the government was

cause for furious discussion that later in fact killed the group spirit that

PLUTO carried into the AABN. The question of sanctions had us in heated debate

hours on end; sanctions against Rhodesia were even more heated. Fighting for

sanctions in a vacuum was in fact acting like pawns in the Dutch government’s

foreign policy objective. By taking government money merely amplified this

fact. The fiction of course was that sanctions were in support of the armed

struggle of the ANC. This the original PLUTO members never accepted: the ANC

was ineffective and riddled by spies, many created by itself through paranoia

that stagnated this liberation movement. We were also saddled with the problem

that taking on sanctions against Rhodesia made of us de-facto mercenaries of

the British government.

So, in conclusion, PLUTO was a handy platform soon drawn into uncharted waters and reduced to a life raft battling to find its ways on a very rough open ocean. This then in the aftermath of Breytenbach's arrest in South Africa and the fallout among the ideological robber barons of the ANC. We were badly placed, or misplaced as whites in some really unexpected cross fire between ANC factions.

Berend

Schuitema

1st December, 2011