Anti-Apartheid Activism in Britain: The AAM, the BEM/BSC and the wider

concerns of the Black community regarding anti-apartheid activism in

Britain

Elizabeth Williams

Birkbeck College, University of

London

In the written accounts of the origins of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement

thus far, we have become familiar with its origins emanating from the initial

boycott of South African goods, and in particular the indelible part played by

South African exiles in shaping and directing the organisation from the late

1950s onwards. However the early influence of Africans and African-Caribbeans

living and studying in Britain upon the precursor to the AAM has not yet been

adequately recorded.

The AAM came out of the Boycott Movement set up in the late 1950s, this

itself sprang from the work of the Committee of African Organisations, set up by

Africans students residing in the UK.

1

Research on the extensive

reach of the work of the CAO is still very much in progress.

2 The

essential facts are as follows: The CAO was formed in March 1958 in London and

was a union of 13 ‘constituent bodies.’

3 The stated six objectives of

the CAO were:

- To work with, and promote the aims of the All-African Peoples Conference, as

well as the Independent African States and to spread among Africans the spirit

of Pan-Africanism

- To work with all constituent organisations and to ensure the fullest

possible cooperation and solidarity on issues affecting the Continent of Africa,

or any particular country.

- To provide an all-African forum for the discussions of matters affecting

Africa.

- To cooperate with other organisations which support the above aims and help

to keep the conscience of the world alive to the problems affecting Africa.

- To work with and provide facilities for, African leaders who visit the UK

for purposes of furthering the struggle against colonialism and imperialism.

- To assist the struggle of our people for freedom liberty, equality and

national independence.4

However Adi has noted that the only published account of the founding of this

organisation is provided by one of the early leaders, Ghanaian Kwesi Armah,

which expresses little about the circumstances that led to its founding or those

who were responsible.

5 However in material published by the CAO on

the occasion of its first congress in 1965 it noted that the organisation was

formed:

As a result of the deep desire among Africans in Britain to have a uniting

body, which would voice out their opinion on African and world events. The

immediate cause of its formation was the passing of the racialist discriminatory

Franchise Bill by the white-dominated Federation of Nyasaland and Rhodesia,

which was awaiting the approval of the British government. From the beginning,

the CAO was an Anti-imperialist and Anti-colonialist Students and Worker’s

Movement. The Movement was effectively organised in this country to contribute

to the struggle for National Independence and Unity.

6

The first headquarters of the CAO was at Warrington Crescent, the site of one

of WASU’s hostels in London. By November 1958 the CAO had established its own

headquarters in Gower Street in central London, in premises also used as a

surgery by Dr David Pitt who would later become Lord Pitt of Hampstead, one of

only three peers of West-Indian origin to sit in the House of Lords in the

twentieth century.

7 The CAO became actively involved in anti-colonial

battles of the time as well as campaigning against the injustices surrounding

racially motivated crimes and issues of the period.

8 Notably its

representatives formed part of a delegation that met with the Home Secretary in

May 1959 calling for more government action and enquiry into racism by a Select

Committee and suggested more active recruitment of black constables into the

police force.

The CAO and the Boycott Campaign

In reaching the decision to launch a boycott campaign to support of the

anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, the CAO was influenced by the ANC’s

spring conference in South Africa during 1959 calling for an international

economic boycott of South African produced goods.

9 The decision of

the All-African People’s Conference held in Accra Ghana December 1958, calling

on independent African countries to impose economic sanctions against South

Africa, may have also played a part in influencing the CAO to launch its

boycott.

11 It launched its boycott sub-committee in May 1959, the

chairman was Femi Okunnu.

11 Other members included representatives

from African student unions based in Britain, and Claudia Jones of the West

Indian Gazette and Rosalyn Ainslie and Steve Naidoo from the South African

Freedom Association. With the exception of Claudia Jones all the members of the

sub-committee were delegates of CAO’s constituent organisations and it held its

meetings at the CAO headquarters at 200 Gower Street. The sub-committee worked

closely with Tennyson Makiwane and with leading members of the CAO-Alao Bashorun

and Denis Phombeah. In writing letters to potential supporters to join and

organise the campaign, Bashorun explained:

The CAO has been asked by the South African National Congress, the South

African Coloured People’s Association and the South African Congress of Trade

Unions, to launch a boycott of all South African goods in this country, in an

attempt to force the Nationalist Government of South Africa to abandon its

policy of racial discrimination and segregation.

12

The CAO called a press conference on 24 June 1959 to maximise publicity for

the boycott campaign, the speakers were Kenyama Chiume and Tennyson Makiwane

followed by a 24hour vigil outside South Africa House. The 26 June the CAO held

a public meeting in Holborn Hall London calling for the boycott of fruit,

cigarettes and imported goods from South Africa.

13 It was agreed to

boycott all South Africa goods sold in the UK as well as protesting in shops

that sold the goods. In following days shopping centres were picketed. Leaflets

issued by the CAO encouraged shoppers to purchase Caribbean, European, and

Australian goods rather than South Africa produce.

14 In July 1959 the

CAO held in conjunction with the Finchley Labour Party, Pickets in North London

as well as in St Pancras, Hampstead and Brixton. It encouraged other

organisations to set up their own protests and courted the support of trade

councils and local Labour Party branches. Support was widespread and demand for

the ‘Boycott Slave Driver’s Goods’ leaflet was so high the CAO began asking

supporters for donations to finance the cost of printing larger

numbers.

15 An important supporter was the Movement for Colonial

Freedom which had contacts and local branches throughout the country, and the

Liberal Party. Adi has noted however that the campaign brought problems, such as

the constant demands for speakers and the increasing demand for more leaflets. A

plan to give prominence to South African brand names in 1959 produced the

problem of possible litigation, and printers refused to print. Criticism had to

be fended off from the national press and various trade organisations. By time

of the a sub-committee meeting at the end of July 1959, it was noted that after

the initial impact of the campaign the CAO had not been able to mobilise enough

forces to broaden and intensify the campaign sufficiently. It was decided to

work harder and gain the support of more ‘eminent sponsors’ as well as

broadening the campaign nationally and internationally.

Restructuring of the Committee in September 1959 brought a new name; the

South African Boycott Committee and new officers.

16 Denis Phoembeah

chaired the meetings, Rosalyn Ainslie of the SAFA, was now secretary, Vella

Pillay of the SA Indian Congress now would act as treasurer. Tennyson Makiwane

recruited Patrick van Rensburg of the SA Liberal Party, who became Director of

what was now the Boycott Movement Campaign by the end of November 1959. Adi has

commented that at this juncture:

Most of those involved were exiled South Africans and although CAO chaired

the committee it was clear that it began to play less of a leading

role.

17

Similarly Gurney notes:

It was becoming clear that if the campaign was to fulfil its potential, the

Committee needed a broader base with more formal representation from a wider

range of British-based organisations…..the Committee was very concerned to

achieve the correct balance between South African and British involvement…this

arrangement of personnel linked satisfactorily South African and English

participation.

18

It was fitting that just as the BMC was about to reconstitute itself as the

Anti-Apartheid Movement, the front page of its publication should acknowledged

that:

…the Movement was first launched by the CAO, who transmitted an appeal from

South Africa in June 1959.

19

The BMC renamed itself the Anti-Apartheid Co-ordinating Committee, then the

Anti-apartheid Committee and finally the Anti-Apartheid Movement in March 1960

just before the Sharpeville massacre galvanized anti-apartheid activism. This

tragedy transformed the nature and direction of the future of anti-apartheid

activism in Britain. Although Gurney has shown anti-apartheid activity had

already been transformed by the work of the CAO and the boycott movement, in

particular during the boycott month-March 1960.

However after Sharpeville the CAO and MCF and the London Boycott Committee

called a protest demonstration in London which saw thousands marching from Hyde

Park to SA House. The CAO sent out its own press releases condemning the

massacre and the banning of the ANC to press agencies worldwide as well as to

international leaders.

In the aftermath of the Sharpeville tragedy the CAO continued to engage in

activities to support the struggle in South Africa. June 1960 saw it organise a

packed meeting to mark South African Freedom Day. In September alongside the AAM

and MCF, and the African Bureau and Christian Action it organised and took part

in a meeting of 700 in Caxton Hall to present the newly created ‘South Africa

United Front’, which included the ANC, PAC, SAIC, SWANC, with speakers including

Tambo, and Dadoo further calls were made to boycott SA produce.

20

Again in 1964 the CAO now renamed the Council of African Organisations

participated with the AAM, ANC and the Committee of Afro-Asian and Caribbean

Organisations to co-ordinate a hunger strike against apartheid. This was part of

a worldwide campaign for the release of political prisoners in South Africa.

However it was the AAM that would emerge as the spearhead for anti-apartheid

activity from the 1960s.

In referring to the CAO and its early influence upon the Boycott Movement

that evolved into the AAM, I wished to demonstrate that there was concern and

active commitment from Africans and people of African descent living in Britain

over the internal affairs of South Africa. This early commitment predated what

would emerge as the mass movement of the anti-apartheid coalition of forces in

Britain, of which the AAM would emerge as the most

effective-organisationally-champion .

The subsequent ‘invisibility’ of black membership of the AAM and the lack of

black officers within its main structures did not mean that black British

concern was not there. Nor that the AAM did not recognise this apparent

disjuncture and did not seek to remedy this state of affairs.

Writing

about Anti-Apartheid activism in the late 1970s one historian in reference to

the apparent apathetic nature of black support commented that:

In the UK, the resident blacks are essentially immigrants, outsiders in the

social system. This group has no immediate revolutionary expectation….the

African liberation leadership while revolutionary is necessarily more concerned

with African than with English society. There is little sense of unity of common

cause between the two groups.

21

This comment fails to acknowledge the long historic tradition of the active

engagement and interaction between continental Africans, African-Americans and

African-Caribbeans and other members of the former British colonies while

residing in Britain.

22 Among the politically conscious in the black

community the unfolding events in South Africa engendered a unique empathetic

understanding of the struggle against the Apartheid regime, an understanding

often not shared by the majority white population. A cursory glance at the

contemporary West Indian papers of the day in particular

The Caribbean

Times and

The West Indian Gazette is evident of this.

23

Sensitivity to what was felt to be unfair treatment and the attempt to draw

parallels with South Africa, can be seen in the reaction to the Government’s

immigration policy of upholding the deportation of illegal immigrants in one

editorial in the

West Indian World:

…….our feeling of security has been shattered….before we walked the streets

of this country as free citizens, entitled to the protection of the law, like

anyone else. It never occurred to any of us that we will be stopped by an

official policeman….like the blacks of South Africa….[and]...have to produce the

British version of the pass-the passport.

24

Even before the significant migrations of West Indians to Britain in the post

war era, black intellectuals and political activists met in London to discuss

the treatment of colonial peoples within the British Empire, they expressed

their concern over the deteriorating conditions of Africans, Asians and Coloured

in South Africa. Though this may not have translated into political action with

concrete gains, the interest was sufficiently strong for invitations to be sent

to invite speakers from South Africa during the series of Pan-African Congresses

that started in 1900 and continued throughout the twentieth century. There were

written declarations of support for Southern Africans struggling under

discriminatory laws and the rest of Africa still under colonialism that showed

an acute understanding of the interconnectivity of the politics of race and

racism across national boundaries. Declarations of intent and protest to HMG

often followed.

The Pan-African congresses brought together Africans and African-Caribbean

and Asian representatives. Sol Plaatje attended the Pan-African Conferences in

Paris and London in 1919 and 1921. At the 1945 conference in London under a

session chaired by WEB Du Bois, Peter Abrahams and Marko Hlubi both members of

the ANC spoke while Professor DDT Jabavu sent greetings from himself and the

President of the ANC at the time Dr A.B. Xuma. Jabavu and his wife tried to

obtain passports to attend but were denied these by the authorities. This

5

th Pan-African Congress moved a resolution regarding South Africa,

it stated that in:

Representing millions of Africans and peoples of African descent throughout

the world, condemns with all its power the policy towards Africans and other

non-Europeans carried out by the Union of SA which, although representing itself

abroad as a democracy with a system of parliamentary government, manifests

essentially the same characteristics as Fascism….this Congress demands for the

non-European citizens of South Africa the immediate practical application

of…..fundamental democratic rights…it pledges itself to work unceasingly with

and on behalf of its non-European brothers in South African until they achieve

the status of freedom and human dignity. This Congress regards the struggle of

our brothers in South Africa as an integral part of the common struggle for

national liberation throughout Africa.

25

In the mid 1950s, Sir Learie Constantine more commonly known as one of the

greatest of West-Indian test cricketers, wrote in detail about the racial

politics of the day in Britain, America, the West Indies or Africa.

26

He notes:

I am afraid it is hard for anyone of my colour to write dispassionately about

what is happening in South Africa today….I will begin by listing some factual

reports from recent South African affairs and making no comment upon

them.

27

However later he allows himself the following polemic:

Coloured nations gaining power and knowledge elsewhere will not for ever sit

idly by watching the progressive degradation without end that coloured people in

Africa now suffer. They will intervene, first (as now) by protest, certainly

later by action. For there is something that all coloured nations share-a

dislike of white Government. It could be a dangerous common factor one day….the

only

final solution in South Africa, to be reached necessarily by

progressive steps, is a condition of exact equality between all colours. They

must be equal in law, in labour, in pay, in opportunity, in political control,

in education and in respect. Even in mutual respect. If white people really

believed themselves superior to black ones, they would not fear such a state,

since then their own vaunted mental superiority would keep them socially and

economically at the top. The fact is that they know that their claimed

superiority will not stand the test of equal opportunity and cannot be sustained

save by bayonets…..I see no eventual objection to a South African Parliament

mainly composed of coloured members representing the coloured majority among the

population. There is no need to deny the whites representation of their own

colour, as they deny the blacks. I see no reason against a Negro Prime Minister

there. If Democracy

means the rule of the people by the people, then

South Africa has no other future-but the result can either be achieved by

tragedy and violence or by wisdom and law.

28

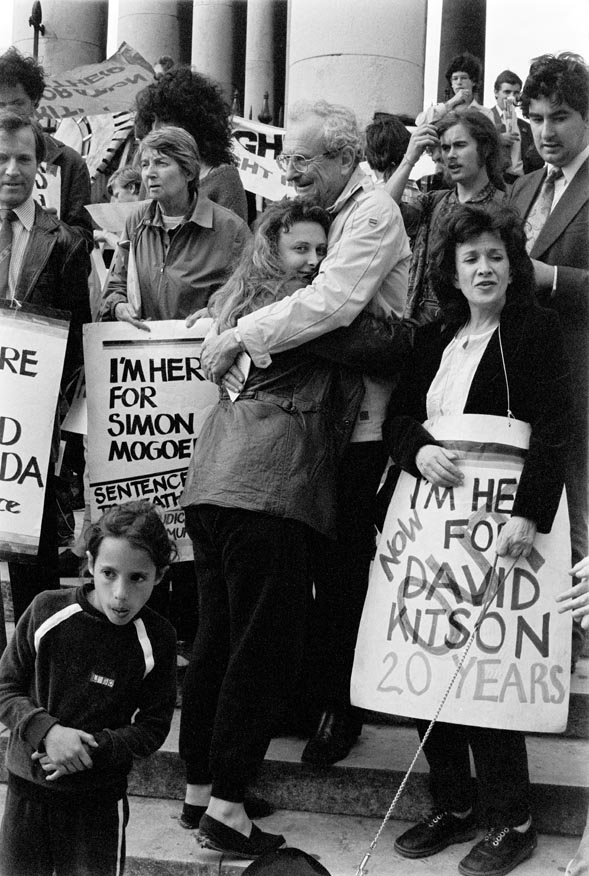

However despite the early work of the COA, and the emergence of the AAM black

faces were notable in their absence from AAM sponsored public events at least

until the Cricket and Rugby tours of the nineteen seventies and later on for the

significant turnout of black people at the anti-Botha demonstrations in 1984

when he came to Britain. How does one account for the apparent irony of the

British AAM fighting to support the struggle to end racism in South Africa while

the domestic black community fighting their own battles of race discrimination

in British society and had a deep empathy with the anti-apartheid struggle, were

noticeable by their low turnout to AAM sponsored events? As current research is

still unfolding, the complexities of black activist involvement with anti-racist

groups and their politics of anti-racism still needs to be examined thoroughly.

As the author continues to examine black involvement in anti-apartheid activism

through interviews with the relevant participants, and examine the available

archives and materials certain considerations are emerging.

Firstly, it is clear when that the apparent low black turnout at AAM

sponsored events during the nineteen seventies and eighties-with a few

exceptions-was not in itself an indication of apathy on the part of members of

the Black community. There has always been an interest and concern about the

fate of Africans in South Africa among the black community in Britain. They felt

a visceral sympathy with peoples that from their vantage point seemed to be

experiencing a not too dissimilar-albeit with its own peculiarities-form of

racism. While ‘Kith and Kin’ is a term often used for the empathy white Britons

may feel for their compatriots settled elsewhere in the world, Blacks in Britain

despite the long trajectory of separation from the African continent and the

cultural, linguistic and religious differences, felt a distinct empathy with

people of colour fighting racism and repression elsewhere.

29

Representing those who became politically conscious of the interconnections

of race across national boundaries, one politician describes it thus:

…emotionally….we always felt that whatever gains we made as black people

elsewhere in Africa, or indeed in the wider diaspora in terms of our freedom, in

terms of our economic advancement, in terms of our political emancipation, it

all counted for nothing so long as the apartheid regime was in place in SA.

Because the suffering of black people in SA, and the fact that for so long the

Apartheid regime got away with it, with the active collision and connivance of

governments in the West, that reduced our humanity. That’s why "Brent-South

today, Soweto tomorrow…….. It was to remind everybody there who at that moment

of triumph for black people and for white people who cared about the creation of

a multi-racial democracy in Britain, was a reminder to them that that counted

for absolutely nothing as long as SA remained under the heel of the apartheid

regime.

30

Furthermore one must recognise the depth of the domestic struggles against

racism in Britain unfolding from the second half of the nineteen seventies.

Black youth in particular could identify Ruth Mompati’s comments, and make

comparison with their own experience in the urban landscape of Britain.

Mompati’s observation relating to life under apartheid:

In South Africa you do not join politics, politics joins you…because your

surroundings is oppressive, people are suppressed, oppressed, brutalised and

this is all in the time you grow up angry-at every turn.

31

Many young blacks by the 1980s did not make academic distinctions between the

racism of apartheid in South Africa and the racial battles they were facing in

the cities of Britain. Linton Kwesi Johnson comments:

….. black people, felt very emotional about South Africa. That was one of the

things that most black people felt strongly about. And for people involved,

activists involved in the black movement in this country, there was a sense that

no matter what, how much progress we make in our own struggles here, as long as

the apartheid system existed in SA black people could not see themselves

anywhere in the world as being really free.

32

Johnson is symbolic of those black youth that came of age politically during

the late 1970s and the 1980s through their struggles against racial

discrimination and clashes with the police. His poetry skilful articulates the

experiences of those on the front-line of this struggle. Referring to the issue

of South Africa he notes:

The issue of South Africa did not politicise me in the 1980s I was

politicised

already. I was as a youngster involved in the Black Panther

Movement [in Britain]. The Black Panther Movement was an organization founded in

the late 1960s. And lasted until the early 1970s, it was an organization

fighting for black rights in this country. In the Black Parents Movement were

immersed in anti-colonial politics so therefore we were involved and had

solidarity with all the anti-colonial struggles going on, including the

anti-colonial struggle in South Africa and the struggle against Apartheid. We

supported the anti-colonial struggle in Angola for independence against the

Portuguese, Mozambique, Guinea and other places. So the question of South Africa

and Apartheid was always there as one of the main issues that black people were

focusing on or people politically involved were focusing upon at that

time.

33

Similarly Professor Stuart Hall symbolises those black activists and

intellectuals who were not only grappling with the domestic anti-racist politics

of the 1970s and 1980s but also had an eye with the wider international

struggles against racial injustice. Hall comments:

South Africa was central to our political concerns from the 1960s.

[Especially] from Soweto onwards. South Africa became a long running problem

from the late 60s onwards… there were people that made those connections, there

were people who were alive to the Southern Africa situation and who were

activists…. people who were black intellectuals and political activists … For

people like me it is partly about race and partly about politics. Partly about

the oppression about people anywhere, part of one’s general sympathy with

oppressed peoples struggling for their freedom and liberty.

34

One historian has argued that though one should not over exaggerate the

parallels that may have been made between the clashes that occurred between

black youth and white policeman during the latter part of the 1970s and during

the 1980s in South Africa and Britain, nevertheless:

In the eighties activists in the front line have shown a…..identification

with the black struggle in South Africa…..the connections between black

oppression in South Africa and inner-city Britain should not be romanticised-the

rule of apartheid is a different order of oppression altogether than the racism

within a democracy, albeit an increasingly authoritarian democracy.

Nevertheless….it cannot fail to be noticed that the government in Britain which

has carried out policies to the detriment of inner-city areas is the same

government which colludes with apartheid in southern Africa. These connections

have produced a participation in traditional forms of political actions amongst

sections of the black community which otherwise operate wholly outside the

reference points of the left…[for example] ..the huge contingent on the

demonstration against Botha’s visit to Britain, which was mobilised by the

Mangrove Community Association.

35

Lee Jasper an activist at the time later to become a leading light in the

National Black Caucus notes:

Obviously the struggles that young black people were going through in the UK

in the early 1980s, resonated with the struggles that were going on in the South

African townships..we began to see pictures of black young people in tremendous

struggles with South African police services, and that resonated with imagery

that we’d already seen in the American civil rights movement in the 1960s, it

resonated with our own experience of policing in largely poor black working

class areas of Liverpool, Manchester, Handsworth, Brixton. And it seemed to have

a universal metaphor for black experience; it was one that viscerally affected

lots of black people in the country. Because it somehow transported us back to a

time when legalised racial oppression was the daily lot of many more people in

the world….so all of those [images]transformed the political consciousness about

the world wide struggle against racism and racial oppression and apartheid

within the minds of the UK black community to a tremendous

extent.

36

If the concern was a great as has been indicated above

where were

black activists directing their energies in reference to anti-apartheid

activity if not directly through membership of the AAM? How and why did they

choose to express their anti-apartheid solidarity in the way that they did? What

were the perceived obstacles to joining the AAM? And what attempts were made by

the AAM-who valued the support of empathetic allies in a largely hostile

political environment-to redress the low level of black participation in the

AAM?

Trying to answer these questions takes us into discussion about the nature

and function of the AAM its priorities and objectives from the 1960s through to

Nelson Mandela’s release. Moreover one cannot overlook the tremendous battles

against racism and inequality that the black community have had to face from the

time they set foot into post-war Britain.

37

Professor Hall has noted that:

….What was happening on the ground was so overwhelming, happening at such a

rapid pace, and intensified so much. Absolutely preoccupying people in their

lived situations., it affected jobs, it affected where they could walk down the

streets, it affected whether their kids would be recognised in schools, it

affected whether you could drive a car and not be stopped by the police. People

were bedded down in those daily struggles, they could also see that it connected

with what was happening in race in Africa, and in what was happening with race

in the US. But what they could do something about was right there in front of

them….it is not a surprise that the overwhelming political energy went into the

building of resistance at a local level, rather than the building of

anti-apartheid politics.

38

Considering the battle that many faced over housing, employment, unfair

treatment over the education of their children, racially motivated crimes,

conflict with the police, sections of the justice system, and the general

hostility from the political establishment down to the man on the street

engendered by the politically charged public debates on race and immigration, it

is amazing that many still found time to involve themselves in anti-apartheid

activities, although noticeably more so from the second half of the 1980s.

Also in trying to account for why blacks did not engage more visibly in AAM

events during the 1970s and 1980s parallels can be drawn with the overall lack

of political participation of ethnic minorities across the board in the British

political arena during the years of their assimilation and consolidation of

their communities while grappling with the shocks of their ‘shattered illusions’

regarding the lived reality of life in Britain.

39 Though

acknowledging the interest that was there, but trying to account for an obvious

short fall of quantifiable interest at least in the AAM itself during the late

1970s and mid 1980s, Professor Stuart Hall has commented:

….the reason why it was so is because black people felt excluded from

political organisations generally and they did not make distinctions necessarily

with those involved in SA because they were largely run by South Africans and by

sympathetic liberals and radical white people in exile….one of their

preoccupations was that these sorts of people in the organisations that they

ran, did not really make common cause with them, so why should they make common

cause with the others?...there is a structural problem…it is similar to the

problem between blacks and the Labour party. The great majority of blacks voted

Labour. Were they involved in the Labour Party? No! They wouldn’t go to

meetings, they wouldn’t pay up because when you said to the labour party "are

you going to help us stop the police knocking our kids around in the streets of

Brixton." They did not want to know. So they felt about many of these

organisations that although they were apparently supporting causes that they

would identify with generally speaking, they couldn’t get organisationally

involved because that was the moment of building black

organisation.

40

However one veteran staff member

41 of the AAM explains that the

reason why the AAM did not engage more fully with the racial politics of black

Britain was due to the fact that the key thinkers within the organisation felt

that the Movement would become ‘distracted’ with British black politics, which

would be counterproductive in the overall objective of the AAM to fight

Apartheid and heighten awareness of its evils in Britain while exerting pressure

on the British government and galvanizing the general public. Some individuals

argued that British blacks and Africans in South Africa had nothing in common

and did not share an affinity. For them the racism of South Africa and Britain

were too dissimilar. Moreover it was apparent that the younger black activists

had a leaning towards the PAC and its ideology regarding the participation of

whites in the struggle, while it was acknowledged that the AAM was more biased

towards the ANC’s with its more inclusive interpretation of the struggle for all

South Africans-black and white, Asian, or so-called ‘coloured.’

However even

though the AAM did not manage to make as deep a connection with the black

community as it would have liked there were many instances before the setting up

of the Black and Ethnic minority committee where the AAM worked with the Black

community, and it was the involvement of the black community that tipped the

balance at Lord’s during the 1970s. The West Indian Standing Conference became

heavily involved during this time and rallied prominent blacks to the

anti-apartheid cause.

42

Similarly a former executive secretary of the AMM disagrees with any

suggestion that the black community may have been apolitical regarding the

African liberation struggle, although it is acknowledged that:

To many in the AAM, black domestic politics seemed volatile and could even

possibly threaten the raison d’être of the AAM if they became too involved in

its anti-racist struggles. While Black radicals for their part were critical of

the AAM’s handling of their allies.

43

It became necessary for the AAM to have a broad church of support however

this often meant that the allies of the AAM presented an area of conflict with

black activists. These allies were often the same individuals in conflict with

black activists over domestic racial concerns. For example members holding

prominent positions in the Labour Party were often strong anti-apartheid

advocates while fundamentally opposed to the moves of radical black Labour

activists to form a black section within the Labour Party. Therefore the power

structure of the AAM may have been dominated by individuals that black activists

felt were their enemies in the realm of domestic British politics.

Even after the Black and Ethnic Minority committee a sub-committee of the AAM

became established precisely to form a bridge between the main body of the

organisation and those black activists that wished to give their support there

was still discontent that the AAM did not concern itself too deeply in the

emerging anti-racist politics of Britain during the eighties. However a member

of the Black and Ethnic Committee of the AAM comments that:

The AAM strategy was not about doing anything with the black people in the

country [UK], it was to get the Government to change its attitude, it was to put

pressure on the Government to stop supporting the regime, that was the whole

focus of the AAM.

For another office holder within the BEM:

[It seemed]… certain members more interested with fighting racism abroad than

at home. However much it was a pragmatic and functional decision/view, it was

decided to let those that wanted to divorce the ‘racisms’ in GB & SA do so.

This would not stop West-Indians from carrying on the fight here [in the UK]

outside of the AAM if needs be….one could not address racism in SA without

addressing it in GB. The bottom line being, the European races in SA were

supported by their kith & kin in Europe. Therefore one could not attack

racism there without attacking the source here. The racism here may not have

been as overt as in South Africa but it was still just as deadly. It was not

necessary that of men in jack boots but those of those in suits and ties. The

ordinary man in the street was the recipient like those in South Africa (who

kept voting in the Nationalists in with increasing number of votes) of the

benefits of racism……[Although ] not all elements within the AAM thought the

racisms should be separated. Unfortunately those who did were the ones that had

the dominant influence within the organization. The attitude seemed to be that

if one wanted an anti-racist organization one should go elsewhere. For them AAM

nothing

to do with anti-racism in discussion of these issues the movement

not as

democratic as it could have been in considering views.

From the above it seems that the nature of anti-racist politics in Britain

posed a potential conflict of interest between AAM priorities and black activist

objectives. Black radicals wanted more action against racism in Britain, while

the AAM’s focus lay with South and Southern Africa. Many within the AAM argued

that the AAM had to be narrow in its focus to meet its objectives.

By the mid to late 1980s after significant anti-racist landmarks were

achieved black activists began to focus more on South Africa and were more

noticeable in their presence at demonstrations. In the aftermath of the urban

revolts and visible governmental and local authority commitment to improving

inequalities many felt emboldened to become more actively involved at various

levels within the political firmament of the society especially after the

introduction of four members into the Houses of Parliament of African-Caribbean

and Asian descent. The level of black community involvement in the AAM through

the work of the Black and Ethnic Minority Committee and other organisations

should be assessed within the context of their wider struggles against racism

and its manifestations in their lived realities of urban Britain. These

struggles also shaped their perspectives on how to counter and combat racial

inequities at home and abroad as well as affecting their relations with white

allies.

The Anti-Apartheid Movement and the Black and Ethnic Minority Committee: The

Beginning

As noted above the Anti-Apartheid Movement was an outgrowth of the Boycott

Movement formed in 1959, its formation was a response to the call by Albert

Luthuli, the President of the African National Congress, for sanctions against

South Africa. From the early 1960s to the 1980s the AAM established itself as

the premier Anti-Apartheid organization operating in Britain. Despite its early

African influences as discussed above it developed and became largely staffed by

South African exiles and émigrés who brought a unique perspective to the racial

problems of Apartheid. They were able to sustain contact with members of the

African National Congress. The ANC’s external operation was conveniently

headquartered in London and therefore provided an alternative perspective to

Pretoria’s propaganda regarding Apartheid.

The first office used by the AAM were within Lord Pitt’s premises, therefore

collaboration with sympathetic individuals of African-Caribbean heritage was

evident from the beginning. From early on the Movement showed an interest to

incorporate substantial numbers of black participants in the structure of the

Movement as well as campaigning for support in the black community, however it

was acknowledged by the late 1970s that:

The AAM is still faced with the difficult task of mobilising in the black

community in Britain. Some developments have taken place but there is much more

to be done in this area.

A few months later the Annual report again noted that:

It is not possible to report any major development in support from the black

community in Britain. Although relations exist with a range of organisations and

they regularly support various AAM initiatives, it remains the case that the

AAM’s work does not make a significant impression in either the West Indian or

Asian communities….However there has been some significant increase in support

form anti-racist organisations. At a local there is usually close liaison

between AA groups and local Anti-Nazi League or similar groups….this area of the

AAM’s work is one which requires much closer attention in the future.

The AAM’s AGM in 1979 had discussed the need to:

secure greater support from the black community in Britain…for a number of

years the AAM has regarded this as an area which needs special attention

Mention was made of encouraging developments such as local groups making

special effort to involve the black groups in campaigning, and the increased

interest from all quarters in the ‘Free Mandela’ campaign. The black newspaper

West Indian World was also singled out for its feature and expanded

coverage of Southern Africa including a front page appeal for support for AAM’s

Free Mandela campaigns. As well as

West Indian World the Black Londoner’s

program featured material from AAM on the main points of the campaign in support

of the patriotic front and publicised the demonstrations and other activities in

London.

However the report notes that thus far:

the most important development" was the commitment of the ANC and black

organizations to campaign to stop the Barbarians tour.

However:

On this and other campaigns the AAM continued to receive valuable support

from Caribbean Labour Solidarity …[However]….it remains the case that the AAM’s

work does not make a significant or lasting impression on either the West Indian

or Asian community and despite the encouraging developments of the last year

there is a need for more work in this area, especially at the local level.

By the early 1980s it was noted that:

Members of the black community in Britain were increasingly involved in the

campaigns of the AAM as well as taking their own initiatives in solidarity with

the liberation struggles in Southern Africa

One initiative was the Mohammed Ali sports development association that

organised a programme of acts for the international year of mobilisation for

sanctions against South Africa. This aimed to involve young black sportsmen and

women in the sports boycott. The AAM was invited to participate at the launch in

Brixton. Black newspapers in particular the

West Indian world and

Caribbean times became notable for carrying extensive reports on numerous

aspects of the campaigning work of the movement.

These papers called on readers to boycott Rowntree-Mackintosh products to

coincide with the AAM’s week of action. And the Black Londoners radio programme

frequently carried interviews with representatives of the liberation Movement as

well as anti-apartheid spokespersons.

Sport became a crucial area of campaigning to engage the interests of the

black community. The Black British Standing Conference against Apartheid sport

founded at the initiative of the Mohammed Ali sports development association

spoke vigorously against the private tour of West Indian cricketers to SA, as

did other British based Caribbean organisations such as the West Indian Standing

Conference. The Standing Conference against Apartheid sport contributed to the

success of the international conference on sanctions against Apartheid sport by

ensuring the participation of black British sportsmen and women.

Activists from the AAM staffed a ‘Free Mandela’ stall at the Notting Hill

carnival originally started to promote the positive aspects of West Indian

popular arts. At subsequent carnivals signatures were collected and campaigning

material distributed.

Black councillors were also active in promoting ‘Apartheid-free Zones’ in

their local authorities. It was noted in the annual AAM report that black

newspapers such as

West Indian World,

The Caribbean Times and the

‘Black Londoners’ radio program were noticeable in their constant support and

publicity given to the AAM and itscampaigns. It was noted that this was in sharp

contrast to most of Fleet street and the broadcasting media. The Channel 4

program ‘Black on Black’ was particularly singled out for praise for its

coverage of events in southern Africa and solidarity campaigns.

The visit of Jesse Jackson in January of 1985 to Trafalgar Square generated a

substantial crowd of people where 25-30% were black. The AAM noted that

Jackson’s engagements gave:

…an important boost to Anti-Apartheid work among the black community."

Jackson addressed a well-attended service in Notting Hill and spoke to

seventy black councillors and community leaders. The meeting was organized at

short notice by Ben Bousquet of the AAM Executive committee. Jackson’s programme

involved meetings with a wide range of organisations and activities in the black

community. This stimulated an increased solidarity within the community. The

Boycott campaign was taken up by local black organizations such as the Black

Parents Movement in Haringey and community groups in Brixton.

The following year the annual report of the AAM noted the ‘Carols for

liberation’ event held in Trafalgar Square which was sponsored by four black

newspapers in London;

The Africa Times, The Asian Times and

Caribbean Times and

The Voice. The Methodist inner city churches

group were also involved. The London community Gospel choir SWAPO singers and

ANC choir lead the singing.

However it was the visit of PW Botha to meet with Prime Minister Margaret

Thatcher in the face of heavy criticism, that caused the black community to come

out in force during the AAM sponsored demonstrations. The AAM continued to

strengthen its links with black groups such as the Black British Standing

Conference against Apartheid sport, the West Indian standing committee, and the

African Liberation committee. Moreover encouraged by significant black presence

at the anti-Botha demonstrations the AAM decided to capitalise on black anger

and discontent over British policy of engagement with the Pretoria regime. The

decision was made to strengthen and deepen contact with black organisations

nationally and locally. The executive committee of the AAM therefore set up a

working party to examine the possibilities of encouraging more members of the

black community to become involved within the structures of the AAM and by

extension encourage greater numbers of the black community to join its

membership. The working party would also examine the perceived obstacles to

black participation.

The AAM annual report notes that the formation and functioning of a working

party represented a watershed in the Movement’s development.

The working party was convened by the Movement’s vice chairperson Dan Thea,

and brought together representatives of local groups from several parts of the

country with activists in the black community. The working party then submitted

its report in November 1987 at the Annual General Meeting. The report

recommended that the Movement give priority to its work in the black community

and establish a standing committee to develop it while committing resources that

would make it possible to give practical effect to the importance attached to

this area of work The 1987 AGM adopted the report of the working party on

recruiting members and support within the black and ethnic community. For the

AAM it:

…Signified an important development in the Movement’s efforts to step up its

work in these areas and to address the concerns that exist, both about the

issues at stake in Southern Africa and about the AAM as an organisation.

The AGM also committed to record that it:

Applauded the contribution made by black and ethnic minority groups to the

work of the movement….noted the successes achieved by anti-apartheid activists

working with local black communities especially in St Paul’s area of Bristol,

Brixton, Edinburgh, Glasgow….recognised that these groups have shown the way in

some key areas of our work..

[and ]Resolved to widen our appeal to and encourage work within the black and

ethnic minority communities."

It was agreed that the clear intention of the Movement in establishing the

BEM committee was to advance solidarity work amongst the Afro-Caribbean and

Asian communities. This report therefore led to the formal establishment of the

Black and Ethnic Minorities Committee. Furthermore the report was used as a

basis of discussion in a number of local Anti-Apartheid groups.

The report frankly discussed the negative perceptions within the black

community of the Anti-Apartheid Movement. According to the report the Movement

was perceived as:

…distant from the black community…all too often seeking to speak for the

liberation movement of South Africa and Namibia.

Antipathy was particularly strong among the black youth who desired to see

the movement involved in more active, radical campaigning-type work. The report

noted:

… [they ]have a view that the AAM exclusively identifies with "only one" of

the South African movements, is opposed to other organisations which may seem

more militant, and ostracises any one who may be seen to support such

organisations."

Moreover it was noted that:

The AAM is often seen as a white middle-class set up, and may even be seen as

standing between Black people and their kith and kin living under apartheid,

tends to hinder the involvement of such people in the activities of the

Movement. There can be resentment at having to give solidarity via an

‘intermediary’-the movement.

In view of this perception the working party counselled that:

This view should not be ignored; rather it requires appropriate response by

the Movement to explain and defend its policies, and to expunge any impression

that the Movement is not so much interested in solidarity with the liberation

struggle in Namibia and South Africa as seeking to have a longer-term,

post-independence political influence in these countries.

Perhaps more damagingly for the AAM the working party reported that the

general consensus among black activities was that the organisation was that:

The AAM..[seemed]disinterested…uninvolved…and even unsympathetic to the

anti-racist struggles in Britain, whilst shouting at the top of its voice how

anti-racist it is in far-off South Africa and Namibia.

To dispel this image the working party instructed that the Movement should

actively be seen to be anti-racist in "theory and practice" and particularly

supportive of anti-racist struggles in Britain.

The working party noted that it saw the:

….the Movement is part of the anti-racist struggle worldwide, and not just in

Namibia and South Africa. We do not accept the fear expressed by some that this

perspective would at all inhibit or reduce the AAM’s capacity to work for the

elimination of the apartheid system. On the contrary, the Movements moral and

material strength would be enhanced by the public and firm acceptance of this

approach.

In answer to the prevailing assumption on the part of members of the AAM that

the black community should find a natural home and affinity within the AAM, it

was noted that it was unrealistic for the Movement to expect that the special

affinity and empathy that Black people in Britain felt for black Southern

Africans should also be equally shown to the AAM. There support could not be

taken for granted in this respect. In the working party’s view:

this affinity is [primarily] reserved for the oppressed people and their

liberation movements.

Interestingly it was noted that:

…the committee did not consider that it should expend too much time

evaluating the perceptions or in assessing the extent to which they are true. We

judged them to be sufficiently accurate for the AGM to have adopted the

resolution which led to the establishment of the working party.

It seems the working party’s task in documenting the disgruntlement and

criticisms of those that kept the AAM at arms length was to provide a window

through which operatives within the AAM could begin to understand why more black

people had not engaged in supporting the organisation in a consistent way. The

BEM would attempt to bridge this gap. After the adoption of the resolutions put

forth by the working party, and the establishment of the BEM as a sub-committee

in its own right within the structure of the AAM, it prepared a document called

‘Call to Action’ which outlined the perspectives of the liberation struggle in

South Africa and Namibia and the role of the Anti-Apartheid Movement. It

stressed the need for solidarity action in the black and ethnic minority

community. Nearly 20,000 copies were distributed at the Notting Hill Carnival of

that year and they were so well received that the National Committee decided

that:

…in view of the importance of the Movement working in this area the brochure

should be made available free to local groups, despite the high costs of

production.

The committee proceeded to discuss means of involving black and ethnic

minority organisations in the Mandela campaigns and an appeal for support was

signed by Bernie Grant MP, the Chair-Dan Thea and Vice-Chair-Suresh Kamath of

the committee. Support for the Mandela’s Marchers from black community

organisations was provided in Leeds, Walsall, Birmingham, Coventry and

Nottingham. The Black and Ethnic Minority Committee’s official launch occurred

on 25 May 1989 in the evening at Soho’s Wag Club. It attracted over 250 people

from a range of organisations. Bernie Grant MP addressed the crowd, and

representatives from SWAPO and ANC were present, including a FRELIMO militant

who gave a defiant speech. Collections for SWAPO’s election appeal amounted to

£600 which was raised with a pledge from The National Black Caucus of £100.

The AAM’s vice-chair-Dan Thea appealed to the black community to continue to

boycott South African goods and get involved in anti-apartheid campaigns. In

August that year the AAM leafleting at the Notting Hill carnival took a further

step, spearheaded by the BEM in collaboration with the London Anti-Apartheid

committee, Women’s committee and Church Action on Namibia, plans were made to

design and staff a float at the Notting Hill Carnival bringing the

anti-apartheid message more overtly to the thousands of revellers that gathered

over the weekend event. The float was designed to promote support for SWAPO.

The BEM in 1990 held a Black Solidarity seminar on 3

rd March in

Brixton. It aimed to present the latest information and analyse the progress of

the liberation struggles in southern Africa. Moreover it sought to create a

forum where suggestions could be made to aid the effectiveness of future

solidarity work in aid of the southern African liberation struggles. A further

purpose of the seminar was to attract and include black activists not normally

involved AAM activities and campaigns. This seminar signified the committee’s

commitment to mobilise members of the black communities in the overall drive for

solidarity support by the British people in the struggle for freedom and

democracy by the victims of apartheid in South Africa.

Black activists involved in anti-apartheid work met to consider the theme

‘South Africa: Countdown to Freedom?’ Bernie Grant MP the keynote speaker gave a

description of his recent trip to South Africa were he met Nelson Mandela on the

day of his release. Sipho-Pityana coordinator of the Nelson Mandela Reception

Committee provided a thought provoking assessment of the emerging new phase in

the liberation struggles. Also present were representatives from the South

African Trade Union and the ANC Women’s section. Members of black organisations

from within Britain were also present. A full report of the day’s events was

circulated to all participants, and distributed to Anti-Apartheid local groups

who were encouraged to use the report and to invite speakers from the BEM

committee.

In 1990 members of the BEM attended a meeting in July as part of a collective

of representatives of the Black community hosted by the ANC to meet Nelson

Mandela on his second visit to London. In his capacity as Deputy President of

the ANC he urged them to play a full part in strengthening the AAM at what he

considered a critical moment of their struggle. He then noted:

We are aware that you the activists and leaders present this morning

represent a large and important constituency. Whilst in prison, we endeavoured

to follow as closely as possible your own battles against racism and

injustice…the thick prison walls...could not prevent us from learning about the

contribution many of you have made to the anti-apartheid struggle…it is our

wish, that at this critical moment in our struggle, the British Anti-Apartheid

Movement should be strengthened. We call on you, dear sisters and brothers, to

play your full part in this noble movement.….we are also conscious of the fact

that in you we have fellow freedom fighters in the struggle to destroy

apartheid….the support and solidarity of people like you, and millions

throughout the World gives us enormous strength and encouragement. There is no

doubt that it has made a significant contribution to ending Apartheid.

The BEM committee tried to raise the profile of its work through

Anti-Apartheid News. Though it sought to appeal primarily to the politically

conscious in the black community, progressive white readership was also

considered. Under the heading of ‘Black Solidarity’ members of the BEM used the

allotted space to discuss issues of race in Britain and South Africa, drawing

parallels as well as providing analysis concerning the democratic future of

South Africa. Through the personal account from one member of West Indian

heritage, describing his visit to Namibia, readers could see how the region was

beginning to open and be accessible to all tourists no matter their skin colour.

The aim was to promote the work of the BEM, attract black readership interest

and engagement, as well as giving the BEM’s own perspective on the debates

concerning racism and anti-racism. For example one member under the heading ‘The

last battle?’ opined:

In countries such as Britain and the USA, where the practice of racial

discrimination has been formally outlawed, black people continue to suffer

disproportionately from humiliation and oppression. What then are the prospects

for SA blacks? The ending of apartheid in its legal forms will mark the end of

white colonialism in Africa. Black people in SA will then have the same old

struggle as the rest of us. [they must]make liberation a reality for the

majority, [and] struggle against class oppression (fuelled by the forces of

international capital), struggle against external and internalised racism..

[and] struggle to ensure that entry into the corridors of power is everybody’s

birthright.

Under another heading, ‘A shared legacy of racism’ the author concurs with

Bernie Grant that the position of black people in Britain and Africans in South

Africa is very different. In South Africa the black majority were enslaved by a

minority government in their own country. In the UK there is a minority of

Blacks and Asians who do not suffer the indignity of legalised racist

policies.

Yet there are similarities as regards the effects of discrimination. The

writer notes that in surveying the black population and its overall position in

British society a disproportionate number inhabit:

Poor, run-down areas, high-rise tower blocks on unpopular council estates,

the ghettoes no one else wanted…a health system which in the 1940s actively

encouraged colonial immigrants to come and work for the ‘Mother Country’, yet

now in the 90s still exhibits a reluctance to cater for the health needs of

those people. Sickle Cell Anaemia and Thalassima are not routinely tested for.

In mental health, racist generalisations label black people as having

schizophrenic tendencies, ‘sectioning’ is used against black people with

resulting deportations. A reputation of ‘under-achievement’ and a legacy of

suspicion remains after immigrant children were channelled into ‘Educationally

subnormal’ schools’ several decades later black students are now better

represented in terms of exam grades, and progression into higher education. But

it brings them little benefit when it comes to gaining employment. Black

graduates have been found to be far less successful than their white

counterparts in getting jobs. Employment agencies connive with racist employers

to impede non-white applicants.

The writer continues to note the desultory fortunes of blacks in the penal

system in comparison to their white counterparts and the poor relations between

the community and the police. Race discrimination at the bar was finally

outlawed in 1990:

This is the reality in Britain where black people have been restricted not by

laws, but by practice.

The writer raises the question as to whether gaining the franchise and being

in the majority in South Africa will ensure black Africans have control over

their circumstances. In making analogy with women who numerically form a

majority in most countries but still do not enjoy the "power and control" of

their male counterparts, the writer infers that the numerical strength of the

black population would not mean they would automatically gain the equality on

par with Europeans as they wish. For instance:

The Race Relations Act in Britain sought to provide a framework to enable

ethnic groups to have equality of opportunity. But the damage and disadvantage

of the past have restricted progress-commitment from the people who have the

power is not there. In South Africa, where the disparities in the conditions and

quality of life are extreme, the legacy of apartheid will live on long after the

last law has been relinquished. The struggle must go on.

The BEM-by now renamed the Black Solidarity Committee organised a ‘Education

for Liberation Conference’ billed as a conference on the role of the UK Black

community in helping to transform education in Southern Africa. Speakers

included prominent black educationalists and representatives from the ANC, and

FLS.

In noting that Apartheid had robbed the educational opportunities from

generations of black people in South Africa-whether through poor quality

education or no education due to political instability the organisers noted

that:

The aim of this workshop is to examine ways in which some of the remedies

found or being sought by the black community in UK could be applied to the

situation in Southern Africa. Solutions would revolve around adult education

such as technical colleges, vocational courses, distance learning, the mass

media, voter education, youth work and positive action programmes…..[and] to

provide an acceptable framework for direct links in terms of mutual benefit.

It was further noted that there was little provision in southern African for

black students with special educational needs. The workshops aimed to focus on

provisions that would be relevant for the southern African context whether

materials or equipment and identify British as well as other international

organisations that might wish to assist adults and children. The radical

ideological thinking behind the conference could be seen through the

conceptualisation of a ‘curriculum for liberation.’ It was noted that:

Black people all over the world have been oppressed by the contents and

language of curriculums as well as the political and economic structures of

education systems….the aim of this workshop is to identify the key issues in

designing curriculum and teaching materials that reflect the rich cultural

heritage of black people. It will examine education under neo colonialism and

ways in which such education legacies can be challenged or reversed. The

workshop will also focus on ways in which teaching in Britain can include the

Southern African experience from a black perspective.

On the 19

th June 1992 a speaking tour was organised by the BEM.

Two ANC speakers were invited-Lawrence Bayana from the Soweto Youth Association

and Kgopotso Sindelo from ANC woman’s league, encouraged by Southall Black

sisters. The tour was part of a national black led initiative involving a number

of organisations. Similarly the National Union of Students Black student’s

conference in Manchester asked a BEM member to speak about its work and the

anti-apartheid activities in light of Mandela’s release.

Concluding Remarks

The Black and Ethnic Minority Committee grew out of a Working Party set up in

fulfilment of an AGM resolution. It aimed to raise the profile of black

activists, and strengthen the campaigning links between the AAM and black and

ethnic minority communities in the struggle against apartheid. The BEM committee

should be seen in the context of the times. The 1987 general election produced

for the first time in British parliamentary history four black members of

parliament; Bernie Grant, Keith Vaz, Paul Boateng, and Diane Abbot. With this

watershed the time seemed ripe for an advance by black activists sharing

sympathies with pressure groups such as the AAM. A key operative within the AAM

at the time has noted that:

Activists fighting racism in diverse ways wanted there to be an effective

campaign against apartheid-the worst manifestation of institutionalised racism

in modern times. The AAM provided it, and when we came in the late 1980s to

focus on the campaign to free Nelson Mandela, support from black activists came

pouring in.

In 1990 the report to the AGM of the AAM commented:

No where has the release of Nelson Mandela and other achievements of the

liberation struggle been welcomed more warmly than in the Black community and by

ethnic minority groups in Britain.