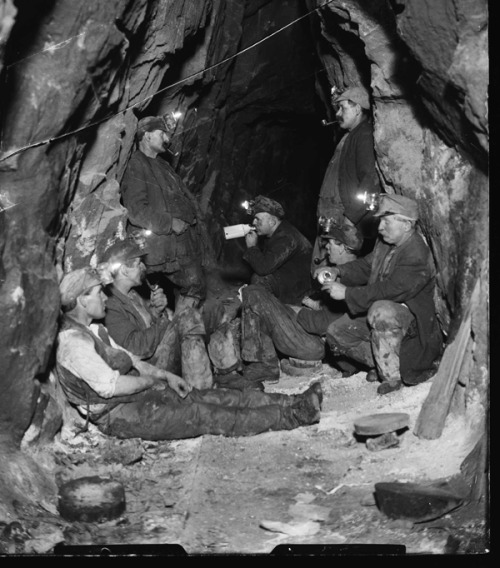

Tin miners taking lunch (Cornwall)

Cornish Miners and the Witwatersrand Gold Mines in South Africa c. 1890-1904

(Published in Cornish History, John Nauright)

Introduction

The economy and society of southern Africa was greatly altered by two developments in the

last third of the nineteenth century. The first was the discovery of diamonds at Kimberley in

1867.1 This discovery took place in an area of land under dispute between the Cape Colony,

the South of African Republic (Transvaal), and the Orange Free State. Due to its economic

dominance, the Cape succeeded in annexing and controlling the new diamond fields. The

fields were rich enough so that in the course of their growth South Africa received its first

massive influx of overseas capital. Even more important was the discovery of what would

prove to be the richest gold fields in the world, on the Witwatersrand in the South African

Republic, later Transvaal, in 1886. Unfortunately for British economic and regional interests,

the gold deposits were located in the center of Afrikaner power in the area, only twenty-five

miles from the South African Republic’s capital, Pretoria. These discoveries completely

transformed the political economy of the region and brought the industrial revolution to South

Africa as well as many new migrants from overseas. The largest identifiable contingent who

came to the Witwatersrand were Cornish miners.

The Rand mines developed differently from all other deep-level mines in the world. This

was due a combination of several factors. First, the ore was the lowest grade of any major gold

field. In order to obtain twenty-one grams of gold, two tons of ore had to be unearthed. Second,

at the time, the price of gold was fixed internationally. Third, much of the gold was located deep

in the earth and its recovery required extensive (and expensive) machinery which had to be

imported from overseas. Fourth, the mine owners also needled skilled deep-level miners in order

to begin mass production of gold. While some of these miners were already in South Africa at

work on the diamond fields of Kimberley or copper mines in the Northern Cape, they mostly

came from the Cornish tin mines, from the coal mines of Northumberland, South Wales and

Australia, and to a lesser degree from various mines in North America. In the early years of

mining development these skilled miners were in great demand as the mine owners were reliant

on their highly specialized skill in order to mine the ore successfully. Therefore, these men could

command relatively high wages. All these factors meant that the costs of production were high

and difficult to control. One means that the mining capitalists used to keep costs down was to

rely on masses of cheap unskilled labor. These labourers were obtained most frequently from the

recently conquered African peoples living in reserves, as well migrants from other regions of

southern and Central Africa. The most reliable source of unskilled African labour was the

Portuguese territory of Mozambique. The use of this massive unskilled black labor force

provided a unique situation for the immigrant skilled miners, as they had not encountered a

similar labour system in any of the other mining areas where they had gained their experience.

This study examines the role of skilled Cornish miners operating in this unique South African context during the years from 1890 to the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910. Particular interest will be paid to the part of these miners in the struggle over, the type of labor policy, and ultimately society, South Africa would become and their role in relation to miners from other areas who came to the Rand. During this period there was a fundamental debate over whether the mines, and indeed the society, would be based on white industrial labor, as in the white settler colonies of Australia and Canada, or would instead be white supervised, supported by the sweat and toil of the black man, or imported Chinese contract workers.

Early analyses of this period concentrated on the mine owners and politicians.1 What little

there was available on the working classes before the 1970s was limited to white labor histories

written by the trade unionists. The most important of these were general histories published in

1926 and 1961, and the biography of trade union leader W.H. Andrews written in the 1940s. (2)

Most of the studies which discuss white workers do so from the perspective of the white

working class’s role in society. The most notable exception to this analysis is Elaine Katz’s A

Trade Union Aristocracy: A History of White Workers in the Transvaal and the General Strike of

1913, published in Johannesburg in 1976.3 Katz’s work is primarily concerned with the leaders

of the white labor movement and white workers’ grievances which led to the major strike of

1913.4 Her work, in the classic labor history tradition, attempts to portray working class

historical development in light of the forward march of labour. Katz’s volume remains the only

full-scale narrative of the early Transvaal labour movement. However, Katz interprets post-war

developments in the Transvaal labour movement as contributory factors which culminate in the

1913 General Strike – white labour’s great (if only temporary) victory over the state-capital

alliance. This interpretation ignores a longer historical progression in the struggle between white

labour and the mining capitalists.

The present study examines the aspirations and concerns of the white working class men

on the Rand, not in terms of a progression towards the great strikes of 1913 or 1922, but rather in

light of their ambiguous position between the mass of African workers and the developing state capital

alliance. Many studies such as Davies (1978) and Jack and Ray Simons (1983), portrayed

English-speaking immigrant miners as a unified group based on class interests.5 While these

workers had similar material goals, it is debatable whether there was a unified movement among

the majority at least until the 1907 strike, and arguably until that of 1913. By this time,

mineonwners no longer were dependent on white miners for their specialized skills so necessary

in the early early years of industrialization. More and more, the role of white mine workers

became predominantly supervisory, and, as they did so, the numbers and roles of Cornish miners

in particular, decreased. They were, however, the largest group of skilled miners during the

1890s and early years of the 1900s. Before discussing Cornish miners in particular, a brief

outline of the industry is necessary.

It was not long after gold was discovered in 1886 that the mines became consolidated in

the hands of a few capitalist groups. By the early 1890s, when the mines began to industrialize,

a unique labor system began to emerge which consisted of a small group of skilled white miners,

paid relatively high wages, and a mass of unskilled African migrant labor, paid very low wages.

The effects of the development of this labor system was to be the dominant force in shaping the

experience of the white working class on the Rand. After the South African War (1899-1902)

this group became more organized and militant as they faced increasing threats to their security

and position. The issues of Chinese importation, de-skilling, and wage reductions,

unemployment, and health began to solidify white working class interests. Trade union

organization progressed slowly in the first few years after the war, but as threats to their position

increased, white miners began to resort to increasing violence, and in 1907 and 1913, major

strikes spread along the Rand.

From early in the industrialization process, white immigrant skilled miners were placed in an

ambiguous position. This group increasingly came under the threat of mining capital in alliance

with the state, from above, and cheap unskilled African labor from below. It was, therefore,

difficult for white skilled labour to ally itself consistently with any other group in the social

framework of Transvaal society. This included opposition to the mass immigration of unskilled

white workers to the Rand prior to 1900. Miners felt that a large group of unskilled white

workers soon would be a direct threat to their position, and especially their wages. They

perceived that unskilled white miners would advance into skilled positions more rapidly than

African laborers. In the 1890s, skilled white immigrant miners were not overly concerned with

threats to their jobs from the mass of African workers, as they knew the mine owners were

dependent on their skill, and could not replace them with unskilled, short-term African contract

labourers.

Immediately after the war, both the mine owners and the new British administration saw

as a key priority the necessity to re-open the mines and attempt to get production back up to prewar

levels. One problem they faced was that there was an acute shortage of African migrant

labour willing to return to the unskilled positions on the mines. Some mines tried white labour

experiments, replacing large numbers of African workers with Europeans. These attempts to

work the mines with white labour met with varying degrees of success.6 However, the majority

of the mine owners decided that the shortage of Africans could best be solved through the

importation of Chinese labourers. This led to a direct controversy with the skilled white miners,

many of whom were vehemently opposed to the importation of Chinese “coolies.” This

opposition, as we shall see, was due in large degree to the agitations of Australian union leaders

who had first-hand experience in dealing with the importation of Chinese workers at home. The

mine owners failed to create united public support for the importation, which directly led to

increased union agitation and organization.7 It was during the campaign against Chinese

importation that many white miners began to promote actively the idea of a white South Africa

in a similar approach taken by the White Australia policy.

During the struggle against importation of Chinese workers, the unions became more

politicized, and rather than join with the party of the mine owners as a unified British interest,

the trade unions allied with the Afrikaner controlled Het Volk party of war leaders Louis Botha

and Jan Smuts. Thus, the British administration and capitalist hope of a unified British interest

against Afrikaner nationalism was smashed by the failure to win union support for importation.

Soon after the Liberal Party won the 1906 British elections, importation of Chinese mine

workers to the Rand was ended. Fighting against the protests of the trade unions, the mine

owners came out with a plethora of reasons to return to the ‘black labour policy’, against the

wishes of the majority of white miners, and the conclusions of the 1907-08 Mining Commission.

The Commission stated that it was economically feasible to work the mines with increased

numbers of white workers, but this would require a substantial initial injection of capital. It was

this that prompted Randlord opposition. The failure of the Het Volk government to force the

mining magnates to implement recommendations made by the commission led trade unionists to

the conclusion that they would not gain political representation unless they formed their own

party. Therefore, in 1909 the South African Labour Party was formed to represent the

aspirations of white labour. By the time of the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910,

the place of white miners in the labour structure of South Africa was firmly entrenched with job

reservation for whites in certain mining occupations.

The Composition of the White working Class on the Rand, 1890-1910

Previous studies of the white working class on the Witwatersrand have noted the diverse nature

of the immigrant white population. These studies, however, have not presented outlines of the

various population groups among these ‘uitlanders’. There was a variety of influences which

helped to shape the attitudes of the white skilled mine workers during this period. The great

majority of the white miners were English-speaking immigrants from Great Britain, particularly

Cornwall, and later from the British settler colonies, primarily Australia.

The first British immigrants to South Africa arrived in the eastern Cape in 1820, and

along with the colony of Natal, founded in 1845, these coastal regions formed the area of

primary settlement by British immigrants prior to the great mineral discoveries. In this period

comparatively little interest was shown towards the interior of South Africa by potential British

immigrants. Only a few farmers, agricultural labourers, and small numbers of skilled artisans

migrated to the Cape and Natal colonies. This began to change after the discovery of diamonds at

Kimberley in 1867, when the demand for skilled mine workers increased. Prior to this there were

only a few English-speaking miners working on the copper mines in Namaqualand in the

northern Cape region which opened in the 1850s. It was only after the discovery of the world’s

largest supply of gold on the Witwatersrand in the South African Republic in 1886 that

significant numbers of English-speaking people began to show an interest in temporary or

permanent settlement in South Africa. The white Afrikaners also responded to the gold

discoveries, as prospectors, later as workers in Johannesburg, and finally as miners on the Rand,

although largely in supervisory roles as they lacked previous mining experience. Interest in

settlement on the Witwatersrand is evidenced in the rapid growth of the primary city on the reef,

Johannesburg, which grew from a few prospectors in 1886 to a city of nearly 100,000 by 1900,

and over 250,000 by 1914. The census figures of the South African Republic and the Union of

South Africa show that a substantial part of this dynamic growth was due to the immigration of

people from England, Scotland, Australia, and other parts of the English-speaking world, as well

as immigrants from eastern Europe, Holland, Italy, and Greece. As a result Johannesburg became

the most cosmopolitan city in Africa. There were communities of Americans, Armenians,

Australians, Bulgarians, British, Belgians, Canadians, Chinese, Dutch, Germans, Indians,

Latvians, Lithuanians, Syrians, and, of course, Africans, English-descended South African

colonists, and Afrikaners. 8

Eric Hobsbawm has called the era of industrial capitalism ‘the greatest migration of

peoples in history’.9 He also stated that people migrate largely for economic reasons, that is to

say because they are poor.10 What must also be added to this is the converse, that people

migrated for the promise of better wages and a higher standard of living. The main attraction of

the Witwatersrand gold mines to immigrant white skilled miners during the period from 1890 to

1910 was that the wages paid there were higher than those paid on any other mines in the world

at the time.

There were certainly both ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors at work in the process of immigration

to South Africa in general, and the Witwatersrand in particular during the last decade of the

nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth centuries. The decade of the 1890s, when the

mines became industrialized at a rapid pace, coincided with a period of depression in England

and Australia, and an acute depression in the Cornish tin mining industry, while the high wages

prevalent on the Rand provided an alternative for skilled white miners.11

In the early stages of deep-level mining, the mines could not function without a

significant number of skilled immigrant miners, as there was not a locally available, adequate

labour force. Even miners who moved from the diamond mines at Kimberley to the Rand were

originally immigrants and not South African born. It is significant to distinguish between the

various segments of the immigrant white population as their previous experiences and

backgrounds were not uniform. In particular, the role of Cornish miners during the 1890s and

early 1900s needs to be outlined as they formed by far the largest group of skilled white workers

on the Rand in this period.

Cornish Miners

Perhaps more has been written about Cornish miners than any other group of miners in the

world. As we shall see, Cornwall supplied the greatest number of skilled white miners to the

Witwatersrand gold mines. It was estimated by a government commission in 1903 at least

twenty-five per-cent of the entire white male workforce on the Rand originated in Cornwall.12

Given that Afrikaners were included in this calculation, Cornish men working on the Rand

would have been considerably greater among the immigrant population. The 1904 Transvaal

census figures show that 35,701 men on the Rand were born in British Europe, while 28,761

were born in southern Africa. The total white male population of the Rand was listed as

71,362.13 These figures suggest, then, that there were approximately 17,500 to 18,000 men from

Cornwall, easily the largest component of the immigrant white working class in the Transvaal.

As the overwhelming majority of Cornish immigrants were skilled miners, their numbers among

this section of the population were especially significant. The fact that Cornwall had not

developed a trade union tradition, and that few Cornishmen can be identified as trade unionists in

the Transvaal, was a key factor in the development of the white working class on the Rand.

By the time the Union of South Africa was established in 1910, many Cornish miners had

returned to Cornwall or moved on to another mining area. This was due to several factors. The

most important were the depression on the Rand from 1903-08 and the mine owners policy of

‘de-skilling’, gradually moving white miners into supervisory roles. After the 1907-08 Mining

Commission Report, there are very few references to a section of the population as being

specifically Cornish. Yet the significance of Cornish miners to the history of white labor on the

Rand is crucial. It was during the period from 1890-1910 that the position of white miners in the

labor structure developed on the Rand was entrenched. The failure of a widespread union

movement to arise before 1907, in large degree, can be attributed to the lack of involvement by

the overwhelming majority of Cornish miners.

The history of mining in Cornwall goes back centuries, and there is evidence which shows

that Cornish tin mines were significant in the period of Roman rule in Britain nearly 2,000 years

ago.14 From the early thirteenth century on Cornwall was the largest European source of tin. Tin

miners were exempt from military service and enjoyed other special rights. Later, copper was

mined at Hayle, from which many miners went to South Africa during the latter half of the

nineteenth century.15 From as early as 1769 Cornish miners were being sought abroad, as

evidenced by the attempts of a secret Portuguese emissary to obtain services of Cornish miners.16

As mining became industrialized in the nineteenth century, along with the rise of international

and imperial capital, opportunities for skilled miners overseas increased. By the latter part of

that century, Cornish miners could be found in places as varied as Wisconsin and Michigan,

Montana, California, Argentina, Chile, British Columbia, Australia and South Africa.17

Gillian Burke identified three main periods of Cornish emigration: to North America in

the 1830s, to Australia in the late 1850s, and to South Africa in the late 1880s and 1890s.18

According to Geoffrey Blainey, Cornish miners were prominent at Ballarat and Bendigo during

the great Australian gold rush of the 1850s, while numerous more “cousin Jacks” worked at the

silver, lead, and zinc mines of Broken Hill.19 In the 1860s the copper fields of Moonta and

Wallaroo in South Australia became known as ‘Little Cornwall’.20 In Montana during the 1880s

a feud between Cornish and Irish miners was a fundamental part of the ‘copper king’ wars.21

Many Cornish miners who migrated to South Africa, as well as to other parts of the world,

left with the intention of eventually returning home to Cornwall. Burke identified two types of

mining migration from Cornwall. The first was that of the ‘single roving miner’ who, if married,

left his wife and family in Cornwall, and who (married or single) returned to Cornwall as often

as possible either to work or while ‘en route’ to another area. The second type was permanent

emigration. This tended to occur during the periods of deepest depression within the Cornish

mining industry, particularly the late 1860s and 1870s, and the late 1880s. In the 1870s about

one-third of the Cornish population emigrated this latter way.22 The Registrar-General in his

report on the 1881 British census, said that the population in Cornwall had diminished by 8.9 per

cent since the 1871 census, and that it was probable that the miners had decreased by twenty-four

per cent.23 Although the first type of emigration predominated, such movements did not

eliminate the possibility of permanent settlement abroad. Some men eventually would send for

their families. Many single men would return to take a bride, usually to keep a house in

Cornwall, although some would take their wives overseas with them.24

The Report on the Health of Cornish Miners of 1904 illustrates the mining migration pattern

clearly. South Africa dominated the report. Of the Cornishmen who had worked abroad, more

than one-half had spent time in South Africa.25 The 1891 British census report stated that

“probably Cornwall contributed a sensible contingent of the 42,990 miners of British or Irish

origin who emigrated from the United Kingdom to overseas mining areas in the course of the ten

years 1881-1891.”26 Unfortunately, the precise extent of Cornish presence on the Rand is

impossible to quantify because all miners were listed under the job classification of mechanics,

and all miners originating in Britain were specified as English and not as being from a particular

county or region. If the estimate loosely calculated above is correct, then approximately 17,500

to 18,000 Cornishmen could have been working on the Rand by 1904. As the 1904 Transvaal

Census lists the male population born in Britain as 31,170, Cornish migrants to the Rand

comprised at least as much as approximately half of the total male immigrant British population

on the Rand at this time.27

There has been general agreement among academics that Cornish miners were far from being

at the forefront of the labour struggle, and that Cornish strikes, industrial unrest, and political

activity were known more for their infrequency, if not by near complete absence. Many look to

the Cornish system of Tribute as the cause of retarded union organization on the Cornish mines.

‘Tribute’ operated on the principle that a miner would work a part of the mine and a percentage

of profit from what was mined was paid to the owner, while a percentage was kept by the miner.

Burke shows that this generalization ignores two key facts. First, the majority of Cornish miners

were not tributers. Second, this overlooks the influence of mining experiences overseas,

particularly the role of Cornish mineworkers in labour organizations.28 Burke suggests, rather,

that it was the influence of returning miners which led to the formation of unions in Cornwall

after 1917.29 Therefore, Cornish miners, while not emanating from a strong union tradition, were

influenced more by their experiences in overseas mining, eventually establishing unions in

Cornwall. However, this did not occur in any great measure until after World War I. A few

Cornish miners, such as Tom Mathews, who had worked in Australia and North America, were

significant figures in the early Transvaal labor movement, although the vast majority of Cornish

miners were not involved in leadership of unions on the Witwatersrand.30

Cornish immigration to South Africa did not begin in late 1880s, but several decades

earlier. The newspaper West Briton of 11 December 1847 was the first to advertise free passages

to South Africa on the Scotia from Plymouth to the Cape for both agricultural laborers and

mechanics.31 The first real influx into South Africa that was of any size and clearly definable as

Cornish commenced in about 1852 when copper mining in Namaqualand began. The mines

were situated immediately south of the Orange River and to the north of Van Rhynsdorp. The

Atlantic Ocean formed the western border of the region, and the districts of Kenhardt and

Calvinia comprised the eastern boundary. There was a brief copper mining mania in 1854-55

when many prospectors and adventurers poured into Namaqualand in search of fortune. Mine

owners made arrangements to bring out Cornish miners, but, by 1856 the copper rush was over.

Some Cornishmen went home, while others stayed on in South Africa, eventually turning up at

Kimberley in the late 1860s.32

By 1870 bullock carts were taking Cornish miners from Cape Town to the diamond mines at

Kimberley, as the Cornish were among the earliest arrivals. Cornish miners who came to

Kimberley in the early stages of mining exploration seem not to be there to make a quick profit

and leave as soon as possible. Rather, the pattern was to work for as long as the mines could

sustain them. Cornishmen were the mining experts of the day, and the opening of the diamond

mines coincided with one of the worst periods of depression in the Cornish mining industry

which occurred in 1866-1870. Cornish miners remained a vital influence at the diamond mines

until 1908 when the Kimberley and Dutoitspan mines were shut down and several thousand

workers were discharged. Many of these Cornishmen returned to Cornwall or went to Australia,

while others moved on to the Rand gold mines. The Union Diamond mines were reopened in

1910, but Cornish influence at Kimberley had reached its high mark in this earlier period.33

Almost as soon as gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand in 1886, Cornish miners arrived

in the Transvaal. Cornish miners were recognizable in Johannesburg when it was no more than a

couple of tin shacks and a half dozen tents. There was evidence in the new mining town of a

substantial Cornish population. Near its center, in the early days, was the well-known ‘Cousin

Jacks’ Corner’, where Cornishmen used to gather on Saturday nights to exchange gossip just as

they did in Cornwall.34 However, by the 1920s, as A.K. Hamilton-Jenkin stated, all had changed

as the physical evidence of a Cornish presence had disappeared: ‘But as the vast buildings

narrowed in the streets, the cheery greetings and homely Cornish talk amid the glitter and roar of

the gold-reef city became as the songs of Zion in a strange land. The rendezvous is now lost

under bricks and mortar, and frequented only by poor wandering ghosts, in search of spirits long

since departed’.35

During the 1890s large numbers of Cornish miners flocked to the Witwatersrand. Every

Friday morning (from 1890-1900) the up-train from West Cornwall included special cars

labelled ‘Southampton’, the embarkation port for South Africa. An old Captain told Bernard

Hollowood when he was documenting his history of the Holman Brothers:

It was a rare sight. At Cambourne station of a Friday the platforms’d be packed

with a great crowd of people, laughin’, cryin’, shoutin’ and so on. Then the train

would steam in slowly and there'd be a great rush for the special carriages labelled

“Southampton”. Then there'd be kissin’ and shakin’ and she’d move out, leaving

the womenfolk and the children wavin’ and sobbin’.36

It is significant to note that the South African Gold Fields Emigrant's Guide published in 1891 by

the Union Steam Ship Company lists only the train fares from London to Southampton, and from

Plymouth (near the Cornish border, and the major train depot for Devon and Cornwall) to

Southampton along with its listing of shipping fares. Also, Cornish passengers received free rail

transport from Plymouth to Southampton. 37 Furthermore, at least one Cornish newspaper carried

a ‘News from Foreign Mining Camps’ column from the 1890s to 1914, which included a

significant number of reports from the Witwatersrand.38

The Witwatersrand proved very attractive to Cornish miners who, by the late 1880s, were

suffering through a period of severe depression in the local tin and copper mining industries.

Although the Rand was attractive economically, it was not without its dangers. According to

A.K. Hamilton-Jenkin, ‘There was plenty of fun, plenty of ‘life’, and niggers to do the work on

the Rand, even though the dread scourge (phthisis) might be biding its time in the dust-filled

stopes where the drills roared out unceasingly’.39 Before the South African War a common

notice on the Rand was: ‘______ , a Cornishman, will be buried tomorrow at 3pm at _________

Cemetary’.40 Still, throughout the 1890s, Cornish miners poured into South Africa. Indeed, the

manager of the George Goch mine stated that ‘Most of the miners of the George Goch are

Cornishmen’.41 Soon the settlements of families around the mines read like the roll-call of a

Cornish village. From Redruth, Cambourne, St. Day, St. Agnes, Beacon, Troon, and all the

mining villages of Cornwall, families were living and intermarrying on the Rand as closely as

they did at home. Even in South Africa local distinctions between Cornish villages continued, as

miners from a particular Cornish village would settle together on the Rand.42 After 1907 Cornish

immigration to South Africa began to decline, and though Cornishmen continued to arrive, the

numbers were greatly diminished as His Majesty’s colonies required financial stability to enter

after this date, and the Transvaal economy was in its fourth year of depression.43 The labor

unrest of 1913 increased the exodus of Cornish miners who had begun to leave as early as the

South African War. Cornish miners who left the Rand went for various reasons, primarily as a

result of the continual ‘de-skilling’ of their jobs by the mine owners, growing militantism in the

labor movement (although some Cornishmen were active in the early labor movement on the

Rand),44 and the improving economic situation in Cornwall.

Labour and the Cornish on the Rand

While many studies of white workers on the Rand begin after the South African War, the

period prior to the war is also significant for several reasons. The first attempts to cut skilled

miners’ wages occured prior to the war as did the origins of the deskilling process. Furthermore,

African workers were receiving longer contracts by the end of the 1890s. All of this led to

mistrust of mine owners by the skilled white miners. It is clear, however, that many miners in

this period did not intend to settle permanently in the Johannesburg area as only 7.9% of them

brought families with them to South Africa. By 1899 there were 10,266 white miners employed

on the mines along with 96,709 Africans.45

As early as 1892, white skilled miners felt threatened by competition from assisted

migrants from Europe and from Africans. This led miners to form the Witwatersrand Mine

Employees’ and Mechanics’ Union (WMEMU) in August of 1892.46 The WMEMU excluded

African workers, only allowing skilled white miners and mechanics to join.

The idea of class isolationism and protectionism was one of the key aspects that shaped

white skilled working class ideology both before and after the South African War. Miners could

literally see changes before their eyes as the African labour force jumped from 40,888 in 1894 to

96,709 in 1899. While white mining employment moved from 5,363 to 10,266 during the same

period, the pace of increase was slower for whites than for Africans.47

For skilled white miners South Africa provided a unique experience. For the first time

they were in a situation where the was a cheap army of labour working for very low wages. This

coupled with the threat from increased immigration led miners towards organization, though the

WMEMU remained small during the 1890s. The WMEMU had some successes such as in the

establishment of the first official colour bar passed in 1893 which made certain jobs for whites

only, though this was eroded by new legislation in 1897.48

The WMEMU served as a valuable beginning to labour organization among whites on

the Rand, securing the colour bar and protecting against the erosion of wages for skilled miners.

The Union was short-lived, however, and was fading away by early 1896. Its strength in terms of

members is hard to determine as membership was kept private. A new Union, the Rand Mine

Workers’ Union formed in 1897 had about 800 members, though it did not last either.49

After the South African War the labour situation on the Rand changed dramatically. Due

to a shortage of African workers returning to work, mine owners decided to import Chinese

workers to take unskilled positions left vacant. This issue deeply divided the white community

though white miners were vulnerable as around 5,000 remained unemployed by the end of

1903.50

White miners returned to work on the Rand gold mines fully conscious of the position

mine owners would take in relation to the running of the mines. Many skilled miners had worked

in the mines during the 1890s. However, it was the arrival of a substantial number of new skilled

miners, particularly from Australia, who injected a spirit of aggression into the labour movement.

The relative numbers of Cornish miners declined during the first decade of the 1900s, while the

number of Australians increased from virtually none to 5000 by 1904.51

The Australian union tradition was much stronger than that of Cornish or other British

miners who had experience in the system of organizing along the lines of the craft union

tradition. By 1890 Australian unions had begun to develop along industrial lines and the

Australian Labor Party was a strong electoral presence. Australian labour also had experience of

the White Australia Policy which only allowed for European migrants to come to the country. In

1902, the Transvaal Engine Drivers cited Australian labour’s campaign against Chinese cabinet

makers as a justification for maintaining the colour bar in the Transvaal mining industry.52

While white labour resisted the importation of Chinese labourers, mine owners were able

to import thousands of Chinese between 1904 and 1908. By 1908 African workers had returned

in sufficient numbers to end the importation. This issue and the maintainence of the colour bar

became paramount after the war as white skilled miners fought a defensive battle to protect their

position on the mines. By this time however, numbers of Cornish miners had declined

dramatically as it was clear that the mine owners preferred deskilling and greater use of cheap

Afrian labour than any increase of the skilled white workforce. While the Mining Industry

Commission of 1907-08 urged greater use of white labour, the government had little will to

challenge the mine owners who were inent of immediate profit maximization.53

Conclusion

While the role of Cornish miners in the early history of mining in South Africa has been

documented previously, the sheer magnitude of their numbers has been not been quantified and

read alongside the overall labour history of the South African Gold Mines. Cornish miners lack

of a strong industrial labour union tradition meant that organization was more difficult before the

South African War than it was after when a large influx of Australian miners with such a

tradition came to the Rand. While some Cornish were active in the WMEMU, its failure to

survive or to gain key economic and political ground can be explained by the inexperience of

miners in trade union organization and politics. While wages remained relatively high at £18 to

£22 a month during the 1890s and certain jobs were reserved for whites, there was a need to

maintain these two areas of strength but little need to be more active during the 1890s. This was

well suited to the Cornish mining experience as opposed to the Australian one. Yet, the role of

Cornish miners in the 1890s was pivotal to the successful establishment of the gold mining

industry and their skills were instrumental in the mines becoming profitable.

NOTES:

1 See W.M. Macmillan, Bantu, Boer and Briton: The Making of the South African Native

Problem (London: Faber and Gwyer, 1929); C.W. deKiewiet, A History of South Africa: Social

and Economic (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1941); Eric Walker, A History of Southern Africa

(London: Longman, 1959); G.H.L. LeMay, British Supremecy in South Africa 1899-1907

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965); T.R.H. Davenport, South Africa: A Modern History, Third

Edition (University of Toronto Press, 1987).

2 E. Gitsham and J.F. Trembath, A First Account of Labour Organization in South Africa

(Durban: South African Typographical Union, 1926); I. Walker and B. Weinbren, 2000

Casualties (Johannesburg: South African Trade Union Council, 1961); R. Cope, Comrade Bill:

The Life and Times of W.H. Andrews (Cape Town: Stewart, 1941).

3 E. Katz, A Trade Union Aristocracy (Johannesburg, 1976).

4 See also: E. Katz, ‘White Workers’ Grievances and the Industrial Colour Bar, 1902-1913’,

South African Journal of Economics, 42, 1974, pp.127-56.

5 J. and R. Simons, Class and Colour in South Africa, 1850-1950 (London: International and

Defence Aid Fund, 1983). Rob Davies describes this study as ‘Marxist historicist’, in that it sees

the history of the white working class in terms of the unfolding consciousness of a particular

class subject. Simons and Simons develop their argument on the white working class in terms of

a dual consciousness—a ‘class consciousness’ and a ‘race consciousness’, with their ‘class

consciousness’ being dominant in this early period. See R. Davies, Capital, State and White

Labor in South Africa, 1900-1960: An Historical Materialist Analysis of Class Formation and

Class Relations (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1979), p. 37, footnote 23.

6 The most notable of the white labor experiments was made by Frederick Hugh Page Creswell,

manager of the Village Main Reef mine. Creswell was opposed by the members of the Chamber

of Mines, who had already come to the conclusion that the best way to achieve rapid return to

pre-war production levels was to import Chinese indentured labor.

7 For more on this issue, see Peter Richardson, Chinese Mine Labour in the Transvaal

(Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1982).

8 Census of the South African Republic, 1891 Report (Pretoria: South African Republic, 1892);

Census of the Transvaal Colony and Swaziland of the 17th April 1904 (London: Waterlow and

Sons, 1906); Census of the Union of South Africa, 1911 (Pretoria: Government Printing Office,

1912).

9 E. Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital 1848-1875 (London: Abacus, 1977), p. 228.

10 Cited in G. Burke, ‘The Cornish Diaspora of the Nineteenth Century’, in S. Marks and P.

Richardson, eds., International Labour Migration: Historical Perspectives (London: Maurice

and Temple Smith for the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, 1984), p. 58.

11 For the general trend and overview, see Burke, ‘The Cornish Diaspora’.

12 Transvaal Government, Report of the Miners’ Phthisis Commission, 1902-1903 (Pretoria,

1903), para. 10.

13 Transvaal Census of 1904, p. viii.

14 G.B. Dickason, Cornish Immigrants to South Africa: The Cousin Jack’s Contribution to the

Development of Mining and Commerce 1820-1920 (Cape Town: A.A. Balkema, 1978), p. 3.

15 Dickason, Cornish Immigrants, pp. 3-6.

16 Dickason, Cornish Immigrants, p. 7.

17 There is a significant literature of Cornish migration in the nineteenth century, for examples

see J. Rowe, Hard Rock Men (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1974); O. Pryor, Australia’s Little

Cornwall (Adelaide: Rugby, 1962); Dickason, Cornish Immigrants; and P. Payton, The Cornish

Overseas (A. Associates, 1999; reissued by Cornwall Editions, Ltd, 2005).

18 Burke, ‘The Cornish Diaspora’, p. 59.

19 G. Blainey, The Rush That Never Ended: A History of Australian Mining (Melbourne:

Melbourne University Press, 1963); G. Blainey, The Rise of Broken Hill (Melbourne: Macmillan,

1968).

20 See Pryor, Australia’s Little Cornwall; P. Payton, A Pictorial History of Australia’s Little

Cornwall (Rigby, 1978).

21 C. B. Glasscock, The War of the Copper Kings (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1935), pp. 74, 114,

133-34.

22 Burke, ‘The Cornish Diaspora’, p. 62.

23 Cited in A.K. Hamilton-Jenkin, The Cornish Miner: An Account of His Life Above and Under

Ground From Early Times (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1927), p. 322.

24 Burke, ‘The Cornish Diaspora’, p. 62.

25 Report on the Health of Cornish Miners (Truro, 1904).

26 British Parliamentary Papers, 1893-94, cvi, C7222, General Census of England and Wales,

1891, v. 4, General Report (London: HMSO, 1892), p. 27.

27 See Report of the Miners’ Phthisis Commission.

28 Burke, ‘The Cornish Diaspora’, p. 66.

29 Burke, ‘The Cornish Diaspora’, p. 66; also see P. Payton, ‘The Cornish Radical Tradition: Its

Background in Cornwall and its Development in South Australia’, University of Adelaide, 1977.

30 Tom Mathews was Secretary of the Transvaal Miners’ Association from 1908 until his death

from phthisis in 1915, see E. Gitsham and J.F. Trimbath, A First Account of Labour

Organization in South Africa (Durban: South African Typographical Union, 1926), p. 160.

31 West Briton, 11 December 1847.

32 The Cornish role in the Namaqualand copper industry is disccused in Dickason, Cornish

Immigrants, pp. 27-40.

33 Dickason, Cornish Immigrants, pp. 47-52.

34 Hamilton-Jenkin, The Cornish Miner, p. 329.

35 Hamilton-Jenkin, The Cornish Miner, p. 329.

36 Quoted in Dickason, Cornish Immigrants, p. 13.

37 W.C. Burnet, compiler, South African Gold Fields Emigrant’s Guide (London: A. White and

Co. For the Union Steam Ship Company, 7th Edition, 1891), p. iii.

38 The Cornishman (Penzance).

39 Hamilton-Jenkin, The Cornish Miner, p. 330.

40 Hamilton-Jenkin, The Cornish Miner, p. 330.

41 E.J. Way, Manager of the George Goch Mine. Minutes of Evidence presented to the Mining

Industry Commission of 1897 (Johnannesburg: Times of the Industrial Commission, 1897), p.41.

42 Hamilton-Jenkin, The Cornish Miner, p. 331.

43 Dickason, Cornish Immigrants, p. 68.

44 Gitsham and Trembath, A First Account of Labour, p. 180; Simons and Simons, Class and

Colour, p. 80.

45 N. Levy, The Foundations of the South African Cheap Labour System (London: Routledge and

Kegan Paul, 1982), p. 82. Figures taken from Chamber of Mines Annual Report.

46 Simons and Simons, Class and Colour, p. 53.

47 Chamber of Mines Annual Report for 1894; Chamber of Mines Annual Report for 1899.

48 Oulined in Simons and Simons, Class and Colour, pp. 55-56.

49 Katz, A Trade Union Aristocracy, p. 22.

50 South African News, 17 February 1904, p. 8; S. Ransome, The Engineer in South Africa: A

Review of the Industrial Situation in South Africa After the War and a Forecast of the

Possibilities of the Country (London, 1903), p. 272.

51 This migration has been discussed by B. Kennedy, A Tale of Two Mining Cities: Johannesburg

and Broken Hill, 1885-1925 (Melbourne: Monash University Press, 1984).

52 Kennedy, Tale of Two Mining Cities, p. 22.

53 See Report of the Mining Industry Commission, 1907-08

No comments:

Post a Comment